The Resurgence of Zine Culture and Niche Publications

Why Print Is Officially Not Dead

The Resurgence of Zine Culture and Niche Publications

The undying question “is print dead?” has been ringing in the ears of big-house publishers for decades. In 2018, fashion giants Glamour and Teen Vogue went completely online while magazine sales in the UK have declined by over 50 percent since 2005.1 Condé Nast—perhaps the biggest name in magazine publishing and home to Vogue, Vanity Fair among others—saw a 43 percent decline in their advertising revenue from 2007 to 2015, as well as further deficits and layoffs following the COVID-19 pandemic.2 Despite frenetically dumping five-hundred million dollars into digital platforms, Condé Nast appears to have no long-term plan in place for combatting digitally-induced obsolescence.3

For smaller “niche” magazines like The Gentlewoman and i-D, the situation could not be more different. In the Business of Fashion article “Why There Are More Fashion Magazines Than Ever,” Chantel Fernandez lists several reasons why these smaller publications are thriving: low overhead, wealthy backers seeking “passion projects,” and brand conscious advertisers, to name a few.4 What appears to be more prevalent, however, is the desire for any non-mainstream media. As the population grows more isolated during the pandemic, the need for meaningful content will only continue to increase. Our digitally fried eyeballs are constantly bombarded with pesky pop-up ads and overloaded hard drives, and an era of no-nonsense media seems long ago and far away. Here we arrive at the early twenty-first-century phenomenon known as the resurgence of the zine and the advent of niche indie magazines. Even more direct and uncluttered than their ad-filled counterparts, zines provide raw, artistically unique content that is unmatched in our daily consumer culture. It is a medium untouched by corporate greed and hyper-capitalist objectives so as to exist only in its pure, democratic form. One can always find like-minded readers and editors in these zine communities as circulation is often limited, making these publications more inclusive and intimate compared to the untouchable giants of Condé Nast. While they are most desired in their printed form, zines have also developed a healthy online and social media presence, keeping them more relevant and accessible in the digital age. Thus, acquiring the best of both worlds from print and digital, zines have decisively become a model for “what the future of media could look like.”5

Zines have been around for a surprisingly long time. According to Julie Bartel, author of From A to Zine, “small chapbooks of Shakespeare’s work; Thomas Paine’s pamphlet, Common Sense; and the myriad leaflets published during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries could all be considered precursors to the modern zine.”6 In 1926, writer Hugo Gernsback started the first ever science-fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, which would later lay the foundation for early zines. Gernsback included a letters column in his publication for fans to debate plotlines and argue about various scientific concepts. After a few issues, he decided to print the addresses of each letter writer so the fans could contact each other directly. This introduced a new means of communication between readers that inspired them to write more and even to form fan clubs. In 1930, one of these fan clubs, the Science Correspondence Club, started an amateur publication called The Comet which became the first ever “fanzine.” Like modern zines, fanzines were published for personal reasons rather than financial ones and became a physical manifestation of a nationwide audience uniting over a beloved subject. Fanzines also struck a chord with the Dadaist and avant-garde movements of the time and gained traction with those searching for unconventional content. Eventually, “fanzine” was shortened to “zine” and a new, idiosyncratic realm of publishing was born.

This rebellious mode of publication found relevance again with the punk youth of the 1970s. Though the 1960s were known for outspoken activism and recreational drug use, the youth of the new decade found what was once rebellious to be stagnant and redolent of old institutions. Thus, the era of punk music began and so did the fashions and lifestyles of the anti-establishment: “As with music, and true to their DIY reputation, when the mainstream media failed to write and publish what they were looking for, punk kids did it themselves, producing zines which featured interviews, record reviews, travelogues, personal stories, and more.”7 By the 1980s, zines had secured an indispensable position in the punk image. Technological advances like the personal computer and affordable photocopying expanded the zine revolution beyond the punk movement and into an “underground network of publishers, editors, writers, and artists.”8

Furthering this concept was science fiction “zinester” Mike Gunderloy, the creator of Factsheet Five. In 1982, Gunderloy standardized his letter-writing by mailing out the same two-page tip sheet instead of responding to each individual reader. This way, he could save some time and disperse his work to a larger audience. After sending roughly a dozen copies, Gunderloy transformed the zine world into an international phenomenon:

Within a couple of years, Factsheet Five, perhaps the most influential zine of all time, grew into a full-size, internationally distributed magazine . . . Chris Dodge explains, “Gunderloy fostered ‘cross-pollination’ not only among zinesters, but also among all sorts of mail artists, cartoonists, poets, and activists hungry for alternatives to mass-produced media.” These new connections between people “on the fringes” of society turned out to be quite powerful, and the underground publishing movement as we know it today was born.9

This communicative aspect of early zines was, and arguably still is, their most compelling feature. For every random interest or specialized field, there exists an entire community that is only a letter (or in today’s world, a click) away. Their self-published existence and individualistic spirit fueled a triumph over an increasingly standardized world of media. Gunderloy’s ability to bring these zines from their quite literal underground existence into the light of popular culture was crucial to the progress of the zine movement; it is ultimately what carried their popularity from the late 1970s and early 1980s into the 1990s and beyond.

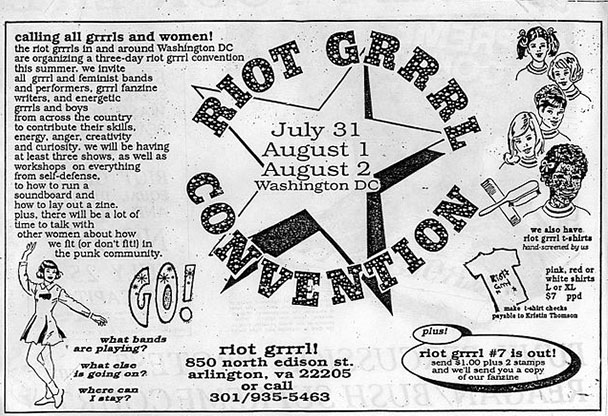

The fitting successor to these grungy punk zines was the riot grrrl scene of the early 1990s. Chloe Arnold’s “Brief History of Zines,” explains how this new era of gender inclusivity responded to its predecessors:

As an alternative to the male-driven punk world of the past, riot grrrl encouraged young girls and women to start their own band, make their own zine, and get their voices heard . . . By 1993, an estimated 40,000 zines were being published in North America alone, many of them devoted to riot grrrl music and politics10

While riot grrrl is most famously associated with its “agro-fem” punk music, it ultimately encompassed a much larger feminist movement. Riot grrrl was created as a response to the so-called “cock rock” world of the 1980s in favor of a more progressive matriarchy. One of the most notable zines to come out of the riot grrrl movement was Bikini Kill, which published the phrase “we are angry at a society that tells us Girl = Dumb, Girl = Bad, Girl = Weak” in its very first issue.11 Its author, Kathleen Hanna, was also the frontwoman of the band Bikini Kill, who famously shouted “girls to the front!” at one of her concerts, and this became the catchphrase of the movement. In 1991, riot grrrl followers organized an all-female punk music festival in Olympia called the International Pop Underground Convention. As the first of its kind, El Hunt hails the festival as “an important example of a space that exists to platform women’s art” and was ultimately the predecessor to Ladyfest, a women’s art and music festival that is still being held today.12 These spunky ladies of the 1990s also importantly coined the phrase “girl power,” the title of Hanna’s second zine, which later became the main slogan of nineties pop and was even adopted by the reigning Queen of Pop, Madonna.

Today, the market for zines and other niche publications encompasses everything from hand-stitched pamphlets to $200 coffee-table books. Upon entering a typical zine website, a reader can very quickly understand its brand and intended audience. Take POLYESTER, for example; the neon pink homepage and collection of dizzying GIFs immediately communicate its cyberfeminist, “no-f**ks-given” aesthetic. If you can make it past the flashing banners and giant heart-shaped cursor, there are several links to point you towards their other ventures like podcasts, future events, and even a subscription service—all plastered with the POLYESTER logo in big bold letters. While still maintaining the intimacy of its predecessors, modern zines like POLYESTER simply use their publications as starting points to establish an entire brand. Now you can buy merch, subscribe to paid content, and attend a selection of annual zine fairs conducted across the globe.

Amidst their increasing brand development, zines have still maintained their status as important vehicles for protest and change. Ever since the 2016 election sparked the era of “fake news,” many grew wary of relying on their go-to news sources for accurate information. Issues of censorship also re-entered media when Donald Trump threatened to ban platforms like TikTok and to launch an FCC investigation into Saturday Night Live, creating an anxious atmosphere for all involved in publishing and media. However, famous for its provocativeness, zine-making remained unbothered by the woes of the “fake news” era; if anything, it fueled them to publish more. Political zines like Rogue Agent and Nasty Woman (yes, it’s even a zine) came full force at the racial and gender affronts repeatedly made by Trump and his administration. George Floyd’s death was another event that sparked outrage from the zine community, creating a swarm of zines solely dedicated to the Black Lives Matter movement and police brutality. Essentially, the distrust in mainstream news caused people to seek out sources that they could more easily relate to. Zines have always held their place in history as a voice for the people as opposed to institutional voices (in this case) like the local and national news. While news stations continued to dwell upon information that repeatedly received backlash from the public (for example, extensively covering identities of mass shooters rather than the victims and the tragedy itself), the zine world remained well in tune with the public’s demands and published content that actually met this criteria.

Though several big-name magazines have also taken a recent interest in political activism, the feedback has not been overwhelmingly positive. The seemingly unanimous theme of 2020’s September issues was activism; from the black contemporary artists on Vogue’s cover to Vanity Fair’s portrait of Breonna Taylor, fashion’s big hitters have decidedly presented a politically engaged front. Though their effort to diversify their content was praised by some, others were not so impressed. Many criticized the media’s participation in the commodification of Breonna Taylor since her death in March. Twitter—a perhaps unexpected platform for social justice issues—was the spotlight for this critique, as one user wrote, “I hope all of the ad money contained in this issue go [sic] directly to the family, and profits from the sales as well. Otherwise, Condé Nast et al are directly profiting from a Black person’s death.”13 Thus, despite the vast exposure from big magazines’ wide-reaching audiences, their ad-packed pages are not having the same effect as the small-budget zine world.

So what are the big guys doing wrong? Let’s talk about paywalls, for starters. Though proven successful in compensating for ad dollars lost to Google and Facebook, they annoy the crap out of average internet users (like myself). In 2017, Harvard Business School professor Doug Chung conducted a study on the effectiveness of advertising and subscription services for both digital and print news sources. In a Forbes article, Chung commented, “If you’re a media firm thinking about pursuing a digital paywall sales strategy . . . you have to make sure you have the reputation and the uniqueness of content to do it, because if you don’t, then you will likely fail.”14 Ultimately, the study did not bode well for the majority of the publications covered. The revenue from digital subscription services was found to be “offset by a significant decrease in digital advertising revenue due to reduced website visits.”15 Because these paywalls heavily reduce website traffic, advertisers are far less likely to do business with sites that have them in place. So nowadays, you either have sites, like Forbes, that plaster pop-up ads across the entire homepage, leaving a faint squiggle of room to read the article, or a paywall that blocks you from reading their articles altogether.

Zines, however, are a relatively different enterprise. Many zines with minimal, local circulation do not have salaried workers or a formal headquarters evidently because the authenticity and passion of their stories takes priority over money. Of course, this means they operate on an entirely different playing field from the heavy hitters at Condé Nast. However, returning to Chung’s findings, which emphasize reputation and unique content, it is perhaps a testament to the originality of these quirky publications that they are immune to heavy declines in advertising sales (no matter the scale of the zine). Additionally, what is unique about the zine is its current and past demand for materiality. Sure, the websites of today’s zines are highly engaging and easily accessible, but members of the zine and indie magazine community are still very adamant about producing and consuming these publications in their printed form—and thus far, through a mix of advertising and self-financing, they’ve been able to afford it. As of late, advertisers have gotten pickier and pickier about who they choose to do business with: “Brune Buonomano, publisher and co-founder of Mastermind, said brands that advertise with publications like theirs are putting themselves in a positive cultural context . . . ‘Brands today have to choose, sculpt, define and handle their cultural footprint because it can be negative.’”16

Because zines are unique in that their goal is rarely to make money, it can be difficult to compare them to the big magazines that are very much fighting for profits in our hyper-capitalist economy. Niche magazines, in contrast, retain a similar anti-establishment spirit to their zine equivalents yet are still situated to generate sizeable profits. Despite these indie magazines’ limited circulation compared to Condé Nast titles, luxury-brand advertisers have partnered with several smaller publications in order to combat their association with corporate greed. In fact, part of the success of these publications is due to their ability to “attract respected or up-and-coming stylists, photographers, and writers eager to prove themselves, offering creative freedom (albeit with low to non-existent budgets, often covered by the photographer themselves). These talents legitimize otherwise obscure publications in the eyes of advertisers.”17 Alternative magazine The Face, for example, was licensed by Gucci, which featured the magazine’s logo on several items for Gucci’s 2019 pre-fall collection, many pieces of which listed for upwards of one thousand dollars. Thus, like zines, niche magazines largely owe their success to their “boutique approach [that] has built a loyal following of both readers and advertisers” as well as to their disassociation with mainstream media.18

Perhaps big magazines did nothing wrong but be the definition of mass-produced media, and for that reason alone become inevitably unfulfilling. Perhaps the success of zines and other niche publications is due less to their innovative style and more to their reputation as a symbol for the disenfranchised. It is precisely for this reason that historically oppressed creatives—such as BIPOC women and LGBTQ+ persons among others—are flocking to small-budget print firms who allow them to work freely without the constraints of a commercial environment, a factor evidently more valuable than its minimal paychecks. The zine has proven to be an unparalleled medium that is highly malleable in form and can thus be shaped to cater to a broad range of audiences. Zines and indie publications have been, are, and will continue to be a symbol of the people as they are unaffected by socio-economic differences and transcend all forms of hierarchy, thus making them a fitting vehicle for the future of print.

- Mark Sweney, “Between the Covers: How the British Fell out of Love with Magazines,” The Guardian, September 14 2019.

- “Can Magazines Survive the Internet?” HBS Digital Initiative, November 18 2016.

- “Can Magazines Survive the Internet?”

- Chantel Fernandez, “Why There Are More Fashion Magazines Than Ever,” Business of Fashion, October 31, 2019.

- Ione Gamble, “How The Internet Revived the Zine Scene,” DAZED Digital, July 32, 2015.

- Julie Bartel, From A to Zine: Building a Winning Zine Collection in Your Library (ALA Editions, 2005), 5).

- Bartel, From A to Zine, 8.

- Bartel, From A to Zine, 8.

- Bartel and Chris Dodge qtd. in Bartel, From A to Zine, 9.

- Chloe Arnold, “A Brief History of Zines,” Mentalfloss, April 16, 2019.

- Kathleen Hanna, Bikini Kill 1, vol. 1 (1991).

- El Hunt “A Brief History of Riot Grrrl – the space-reclaiming 90s punk movement,” August 27, 2019.

- dissociative director, @vaendiskona, Twitter, August 24, 2020, https://twitter.com/vaendiskona/status/1297869935557971968.

- Doug Chun quoted in Kristen Senz, “Why Paywalls Aren’t Always The Answer For Newspapers,” Forbes, August 1, 2019.

- Senz, “Why Paywalls Aren’t Always The Answer For Newspapers.”

- Brune Buonomano quoted in Fernandez, “Why There Are More Fashion Magazines Than Ever.”

- Fernandez, “Why There Are More Fashion Magazines Than Ever.

- Fernandez, “Why There Are More Fashion Magazines Than Ever.“