That’s really what I want to get at with this project: the hope that keeps people waiting.

The Ones Who Wait

For my final project I wanted to focus on the idea of waiting. My two main sources of inspiration were Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett and an excerpt from Tom Lutz’s Doing Nothing about freetahs in Japan. In this anecdote from Lutz’s book, he retells a conversation he had with a Japanese bartender about freetahs. The bartender explained that there are different categories of freetahs, or slackers, and the one that struck me the most was the one she called “The Dream.”1 She describes this as someone who is aspiring towards a goal, generally an artistic one, but in the meantime is not doing much of anything. I thought this description of this kind of waiting was very romantic and intriguing, and it also went along with what I wanted to incorporate from Waiting for Godot. In the first act of the play, Vladimir and Estragon are discussing what exactly they are expecting from Godot, and decide that they asked of him “A kind of prayer,” but that “he couldn’t promise anything,”2 and yet they wait for him day in and day out. That’s really what I want to get at with this project: the hope that keeps people waiting.

I discovered an editorial by Craig Jeffery in the Journal of Environment and Planning D: Space and Society, in which Jeffery describes the difference between waiting for an “abstract future” and waiting for “the forth-coming. . . .consequences of routine actions.”3 An “abstract future” would be like “the Dream” for freetahs, whereas “the forth-coming” would be like a paycheck for the work you did that week. In Mikio Fujita’s article “Modes of Waiting,” Fujita outlines three different things that are waited for: the first is, mechanical or technological things; the second is things of nature; and the third is “the world of becoming.”4 The one that I’m mainly focused on is the third, which Fujita describes as, “the one in which we become ourselves; the world where our understanding, expression, and creation takes place; the particularly human world in and through which we become more human.”5

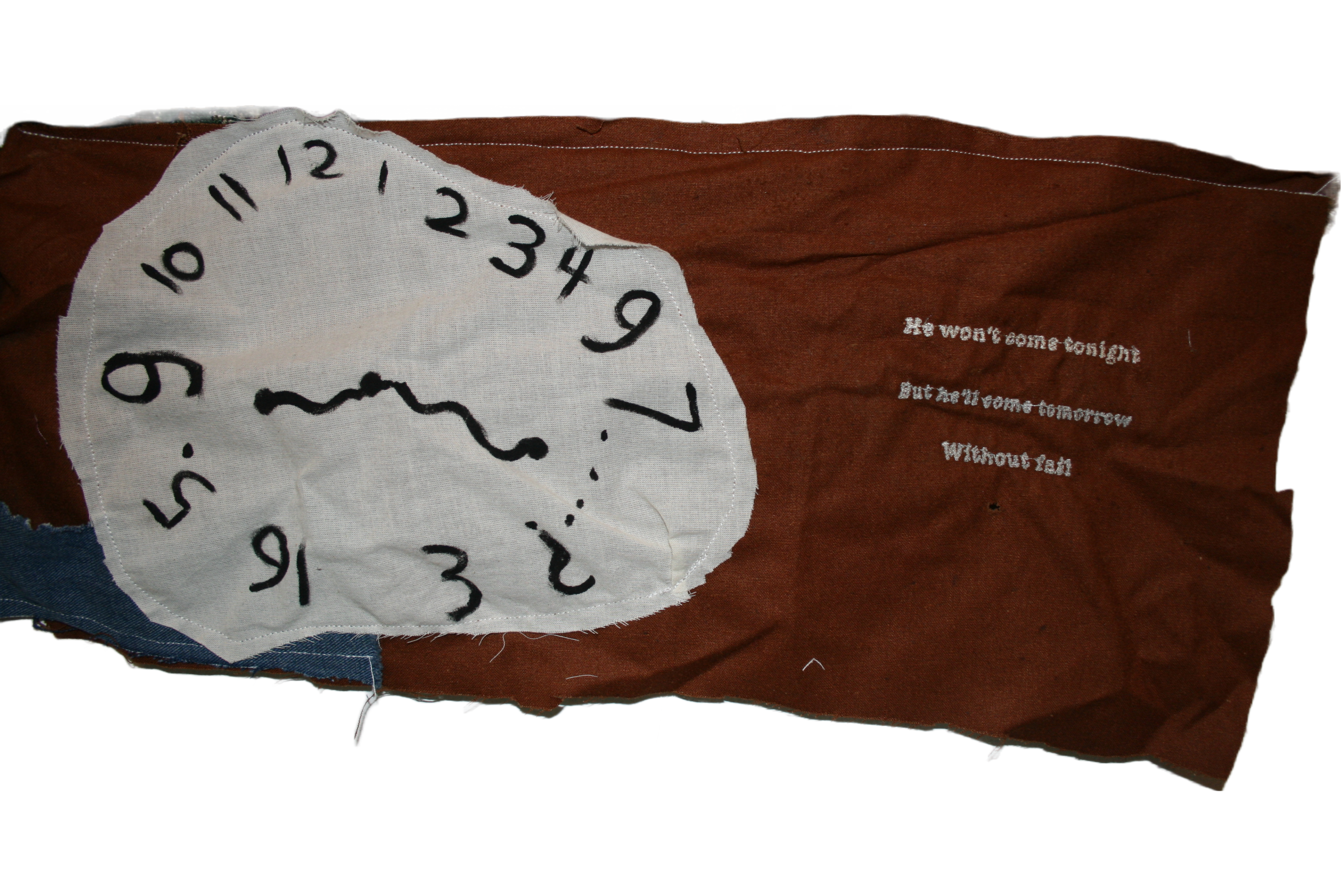

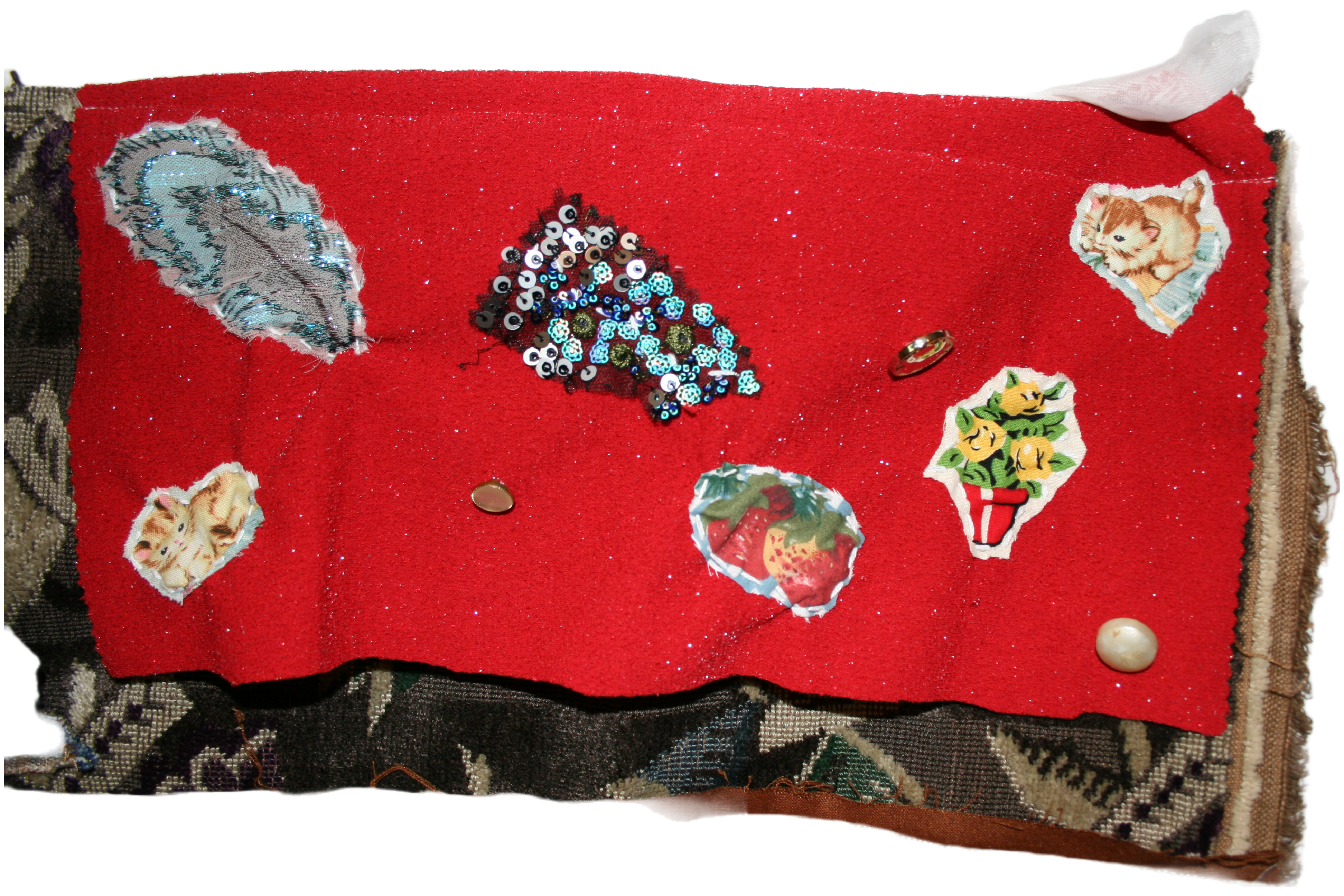

To bring all these thoughts and ideas together, I decided to make a tapestry (pictured below) that acts as a sort of character sketch of the ones who wait. Since I was mainly drawing inspiration from Waiting for Godot, I wanted to use coarser, lower-quality fabrics to represent the socioeconomic status of Vladimir and Estragon and particularly to use that to contrast the other section of the tapestry that represents their hoped-for future. The “future” section is in the top right corner, and is covered by a translucent piece of fabric to represent the abstractness of it and to show that it might always be just out of reach. This, I think, relates to Fujita’s writing about becoming, because we never truly stop becoming something else, so it’s hard to really say that you’ve reached that point of having become something permanently. I also included a quote from Waiting for Godot in the bottom right corner which says, “VLADIMIR: He won’t come this evening. . . .But he’ll come tomorrow. . . .Without fail.”6 I feel like this quote encapsulates the heart of my feelings about waiting: it shows the hope that Vladimir has that something will change for the better, but also the futility of waiting for something that might not ever come. I feel like that is a very human experience that we should all consider and keep in our hearts.

- Lutz, Tom. Doing Nothing. Macmillan, 2006.

- Beckett, Samuel. Waiting for Godot. Grove Press, 2012.

- Jeffery, Craig. “Waiting.” Editorial. Journal of Environment and Planning D: Space and Society, vol. 28, 2008, pp. 954-958.

- Fujita, Mikio. “Modes of Doing Nothing.” University of Alberta Journal of Phenomenology and Pedagogy, vol. 3, no. 2, 1985, pp. 107-115.

- Fujita, “Modes of Doing Nothing.”

- Beckett, Samuel. Waiting for Godot. Grove Press, 2012.