A Psychogeological Analysis of Lower Manhattan

What’s Underneath

A Psychogeological Analysis of Lower Manhattan

Introduction

New York City is disconnected from all things natural; mention of the city conjures up images of looming skyscrapers, bustling sidewalks, and endless traffic—all things that have been made by man. The natural earth has been smothered by concrete sidewalks and blue skies are pierced by tall buildings. Perhaps some people will picture Central Park and its sprawling green fields, but even that lush green space has been deliberately planned and manufactured by humans. Few will think of the natural landscape that is the root from which all New York’s skyscrapers stem and that dictates all of the city’s infrastructure. The Earth’s movements millions of years ago have created the city we know today, and it is to these invisible forces that we owe the city’s bustling and uniquely built urban atmosphere.

In this paper, I explore how the geology of Manhattan informs how contemporary people experience the city. I am intrigued by how seemingly insignificant events in the Earth’s history and small movements in the Earth’s crust can affect the overall ambiance of certain areas of the city. And yet, I believe that the disconnect between Manhattan and its natural environment extends to its geology. In order to explore this theory, I first outline the specific forces of nature that created Manhattan and the different types of rocks that can be found underneath the city. I give an overview of the style of exploration that I used to test my hypothesis, a school of thought that is known as psychogeography. I discuss the various research projects and theorists that influenced my own work. I outline my methodology and describe my findings from a case study. Finally, I analyze my findings as well as the conclusions I have drawn.

Manhattan’s Geology

Millions of years ago, movements in the Earth uniquely formed the land we now know as Manhattan. When the Taconian Orogeny occurred sometime between 450 million and a billion years ago, the piece of land now known as North America collided with a chain of volcanic islands and was slowly pulled under these islands.1 The immense amount of pressure exerted onto the North American land caused it to metamorphose and fold into itself, thus creating the metamorphic rocks that make up Manhattan today. A metamorphic rock is a type of rock created when one rock undergoes such immense pressure and heat that it turns into a new type of rock. In this way, limestone became Inwood marble, shale became Manhattan schist, and these two new rocks were folded in with the already existing Fordham gneiss.2 These three types of rock make up the three layers of Manhattan’s underground; however, many more continental shifts and Earth movements still had to occur before the Earth became the one we know today, as the metamorphosis of these rocks occurred pre-Pangea. Nevertheless, North America’s chance collision with that collection of volcanic islands millions of years ago has dictated the built environment on Manhattan, including where certain building types can be placed.

The specific layering of the metamorphic rocks across Manhattan determines what types of buildings can be built, and thus informs how its inhabitants move through and feel in various areas of the island. Manhattan schist is the strongest and most durable of the three rocks, and thus it is necessary for the towering skyscrapers that characterize Manhattan. However, because of the Taconian Orogeny, Manhattan schist was folded into the other two types of metamorphic rocks and thus appears at various depths throughout the island. This variety in depth is partially why there are no skyscrapers in the middle section of the Manhattan skyline. At the southern end of Manhattan, schist is just twenty-six feet below the surface, however, as you move north, the schist levels dip into what is known as the Bedrock Valley, where schist is up to 150 feet below the surface between City Hall and Canal Street.3 As you continue north, the schist levels rise again and stay relatively close to the surface, even coming above ground in areas of Central Park now used for relaxing and leisurely picnics.4 Although not the main contributor to skyscraper heights in Manhattan, the varying levels of Manhattan schist somewhat dictate what types of buildings can be built where and thus what types of atmosphere that corresponding area will have. Jason Barr’s research showed me that depth to bedrock was not the only determining factor in Manhattan’s skyline between the years of 1890 to 1915. There is a wide belief that the lack of skyscrapers between Wall Street and Midtown business districts exists because of the Bedrock Valley, and thus builders did not want to go to the effort to spend the money to reach the deeper bedrock.5 However, Barr found that the deeper bedrock was not as significant a limiting factor as people think, only causing a 7 percent average increase in construction cost.6 Rather, skyscraper location was based on proximity to transportation, land value, native white population, and proximity to greenspaces.7 Thus, Barr’s research helped me to understand that while geology is a significant determining factor in where skyscrapers can be built, it is not the only factor. With these researchers’ findings in mind and a new perspective on psychogeography, I set off to develop my own study that would help me better understand how geology influences urban atmospheres.

Psychogeography

For my research, it is imperative to understand the study and exploration of how a place’s geography informs how one moves through the area, a field known as psychogeography. Linked to twentieth-century French Marxist theorist Guy Debord, psychogeography is defined as, “the study of the exact laws and specific effects of geographical environments, whether consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals.”8 Psychogeography is concerned with interrogating the everyday occurrences that we accept as matters of chance: it aims to find the answers to why certain streets engender anxiety or how certain blocks of a city can completely change in ambiance as you walk along.9

Key theorists in psychogeography, such as Debord and contemporary writer Will Self, conduct their research through walking. Self, who in his text Psychogeography walks from his home in London to the Lower East Side of Manhattan, was influential to my own research. Not only is his journey in and of itself unique, his narrative style of writing truly keys the reader in on his thoughts as if they are there with him in real time. Alongside Self the reader tackles issues such as walking from JFK International Airport to his hotel in an area that was designed strictly for vehicles, walking without a map, and how geographical features can inspire nostalgia. Furthermore, Self discusses the concept of “interior-exteriority” and how our personal issues can be aggravated by our environments.10 Self discusses how he journeys to Manhattan to connect with the geography in the way his late mother, who was born there, would have. In this way, psychogeography is a personal endeavour. Nonetheless, Debord talks of issues that seem generalized and universal:

The sudden change of ambience in a street within the space of a few meters; the evident division of a city into zones of distinct psychic atmospheres; the path of least resistance that is automatically followed in aimless strolls (and which has no relation to the physical contour of the terrain); the appealing or repelling character of certain places these phenomena all seem to be neglected.11 Self builds on Debord to show that psychogeography is also a look inward.

Contemporary archeologist Kenneth Brophy furthers the study of psychogeography to encompass geology in his study of how citizens interact with traces of prehistoric archaeological monuments in urban spaces. In looking at prehistoric remnants in Scotland such as the Sighthill Stone Circle, Brophy is able to develop a deeper understanding of how these seemingly empty places devoid of sentimental or nostalgic value for the current population take on new meaning as they are interwoven into urban life. Sighthill Stone Circle, for example, exists in a microcosm of Glasgow urbanity—it is 100 meters from the highway, surrounded by high-rise residential buildings, next to a canal and industrial infrastructure.12 This inundation of urbanity has given the prehistoric site new meaning, however, and it is now a prime location for teenage nightlife and the occasional dog walker. Brophy conducted his research by walking around aimlessly for hours at these prehistoric monuments, and sees psychogeography as something uncomfortable but necessary. Psychogeographic exploration may be uncomfortable because your body is so disciplined to move in urban spaces in a specific way: Cities demand a destination and an uninterrupted path, and thus standing on traffic islands for long periods of time or retracing your steps may feel awkward.13 With these three approaches to psychogeography in mind, I set out to develop my own study in psychogeology.

Methodology

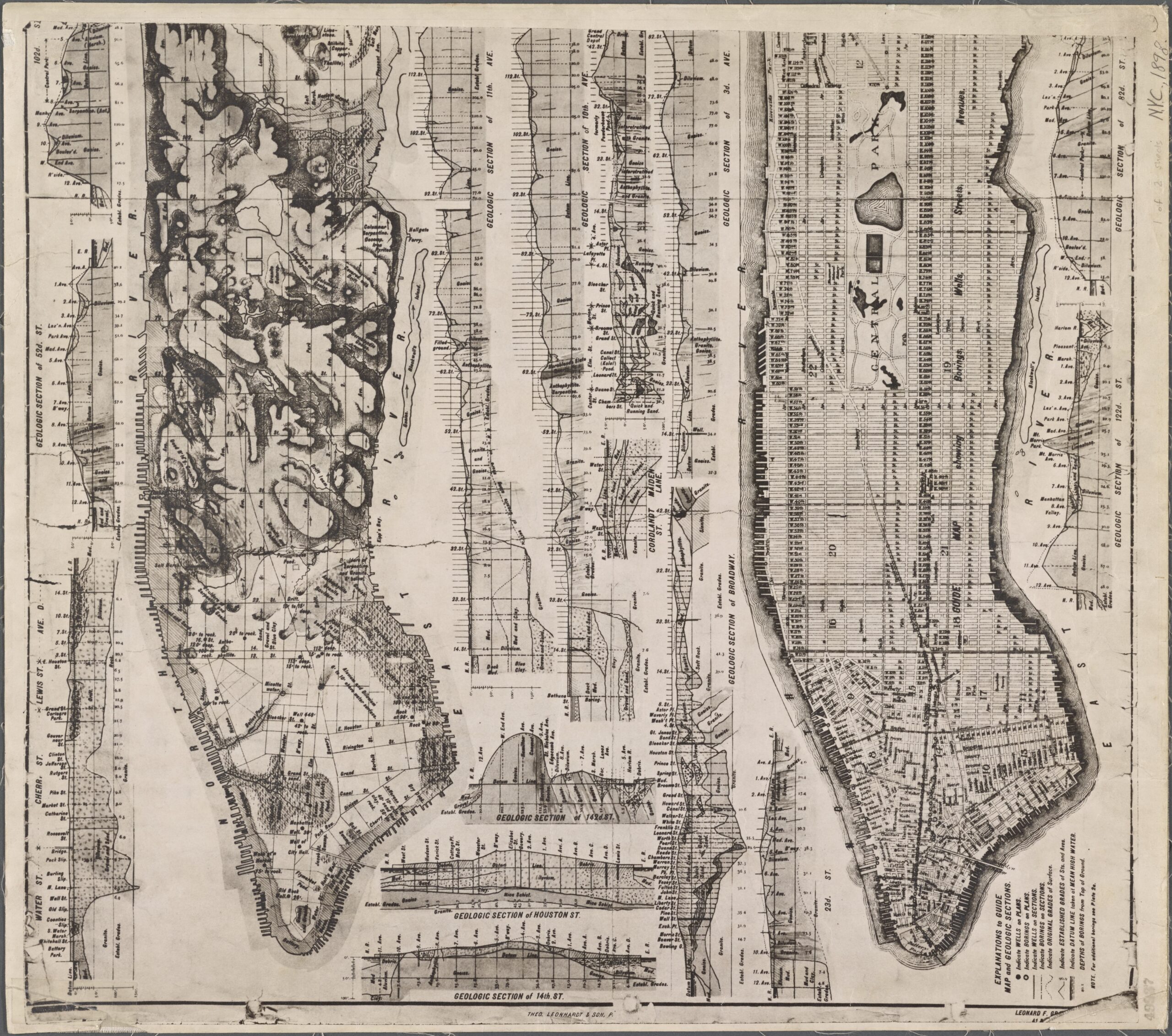

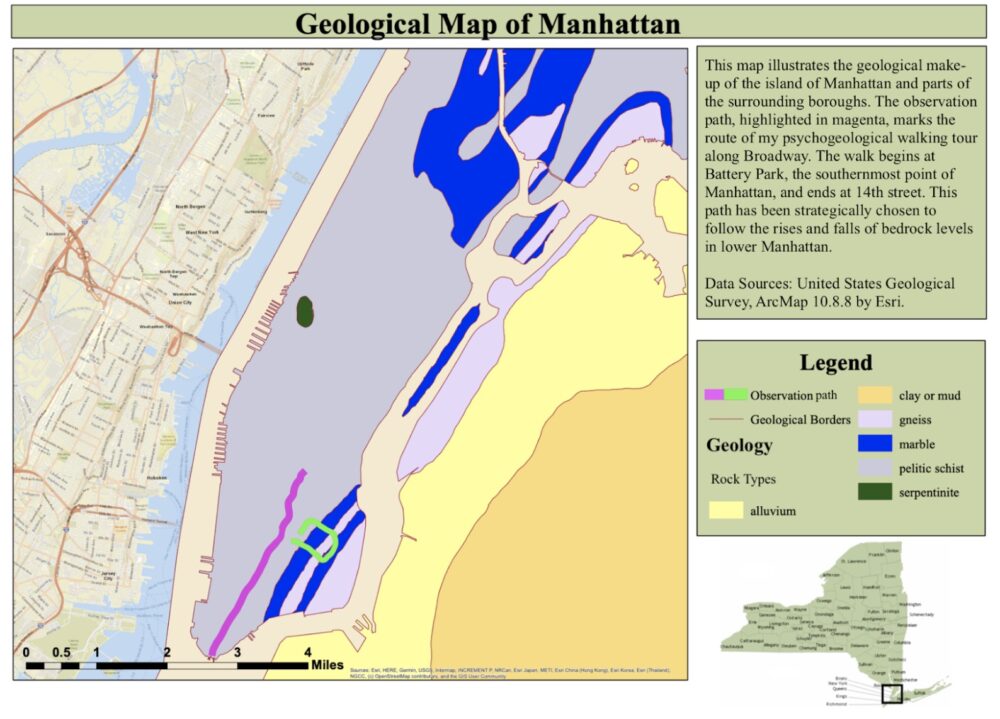

In order to explore how the geology of Manhattan affected the ambiance of certain areas, I first needed to develop a better understanding of the exact locations where the geology shifted and where bedrock depths varied across the city. To do so, I compared the information presented by Barr to a historic map created by Lionel Pincus as well as doing my own analysis of New York geological data in the mapping program ArcGIS. Pincus’s map, created in 1898, offers a clear depiction of the geological makeup of Manhattan as well as includes cross sections of major streets across the city.

For example, he illustrates the depth of bedrock on Broadway from the southern tip of Manhattan to Forty-Fifth Street, labeling each cross street as well as other types of rocks found above or underneath the bedrock. Pincus does not include Manhattan schist specifically on his geological map, and I believe this is because Manhattan schist was not discovered until after Pincus published his map. In Geological History of Manhattan, or New York Island, a guidebook to Manhattan’s geology for American students by Issachar Cozzens, written in 1843, Cozzens outlines every type of rock to be found under the island of Manhattan, yet he also fails to mention anything on schist. This leads me to believe that geologists had not excavated Manhattan schist during the 1800s. However, I confirmed the location of Manhattan schist with my own map rendered in ArcGIS. My map clearly depicts where pelitic (Manhattan) schist is located, as well as where other geological shifts occur.

With this information and the research of the psychogeographers in mind, I chose two areas to conduct my own fieldwork in. The first is located in the East Village and represented on my map by the green near-rectangle. I chose this path because I was interested in seeing how the shift from Manhattan schist to Inwood marble to Fordham gneiss would alter how the environment is perceived. Unfortunately, the length of this research project was too short to report my findings on this case study, and as my next case study was more fruitful, I decided to solely report on that. My next area of study is highlighted in magenta. Inspired by Self’s walk from London to New York, I decided to walk from the southern tip of Manhattan, through the Bedrock Valley, and end at Fourteenth Street. I chose this route not only because it followed the increase and decrease in bedrock across lower Manhattan, but also because Broadway is one of the streets with clear geological cross-sections in Pincus’s map. Finally, I set the intentions for my psychogeological analysis. Again, inspired by Self’s own psychogeographical writing, I decided that I would observe only how I was perceiving the environment instead of attempting to draw conclusions on how others were interacting with urban geography around me. I felt that by using myself as a subject, I would be able to draw more precise conclusions as well as be able to gather better data in shorter amounts of time. It was already quite labor intensive to conduct walking tours by myself and continuously transcribe my thoughts while doing so, and I believed it would be even more difficult to attempt to observe and make sense of others’ movements in that process.

I titled this style of observation “psychogeology” because it looks beyond the geography of the land and aims to analyze the effects of what is underneath the surface. While Debord defines psychogeography as “the study of the exact laws and specific effects of geographical environments, whether consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals,” I would define psychogeology as the study of the specific effects of the geological makeup on the emotions and behavior of individuals.14

Results of Broadway Walking Tour

I took the subway down from Union Square to Battery Park to begin my journey. Already I was at more of an advantage than the psychogeographers whose works I had read: I had a map, note taking device, camera, and search engine all in my back pocket, and thus I could easily navigate through city, capture pictures to remember by experience by, and track where I had walked to refer back to in my write up.

As I arrived in Battery Park, I was struck by the sheer magnitude of the city as I stared out at it from the southernmost point of the island. The skyscrapers loomed over me and their height was awe inspiring. As I walked up Broadway, I kept in mind that the bedrock was closest to the surface here. At the edge of Battery Park, the city felt so grand. As I moved deeper into the city, however, the Gilded Age architecture intersected with modern skyscrapers to form an interesting layering of history that situated me within time in a way I was not familiar with. The grand stone columns of the National Museum of the American Indian juxtaposed the loud beeps of the taxis and the hustle of the Wall Street area. Behind Trinity Church stands a geometric modern building. These strange intersections left me feeling confused—in the area of Manhattan that I was most familiar with, Greenwich Village, there seemed to be a collective agreement among the architects that buildings there would be made with brick and would suit a certain style. In the Wall Street area, however, the hodgepodge of architectural styles was utterly confusing and, combined with the chaos of the commercial area, left me feeling anxious. I could not decide where to look or what areas of the landscape deserved my attention because they were all uniquely interesting.

A photograph taken at the corner of Cortlandt and Broadway depicts this palimpsest perfectly. There is a modern glass facade, an Urban Outfitters, a romanesque revival style brick building with arched windows and red trim, a modern skyscraper, a construction site, and an oncoming bus all in one frame. Similarly, I noticed a lot more scaffolding as I walked uptown, which left me feeling disconnected from nature, as the sky was barely visible. The additional construction sites also added to the din of the area. Even when I was not underneath scaffolding the sky was punctured by the many skyscrapers. Another thing I observed was the overall din and mass of people in this area was quite unusual. There were businessmen, old women with walkers, crowds of tourists, young people, babies, and everyday citizens all in one space. To add to the chaos, there were an absurd number of memorials and historical markers. On the sidewalks, in graveyards, in the green spaces, at Wall Street, and on the sides of buildings there always seemed to be some sort of memorial to read or gaze upon. Perhaps this is why there were many tourist groups and constant giant NYC Tour busses passing by. Overall, the large buildings, various architecture styles, strange crowds, construction, and never-ending traffic made the area between Battery Park and City Hall quite overwhelming. There was so much to take in that I found it difficult to not get distracted as I was walking. Had I followed my feet and my eyes, I never would have escaped the labyrinth of the area between Battery Park and City Hall. Additionally, my sense of time felt altered by the memorials, varied architecture, and disconnect from nature. The myriad of historical markers and intersection of architectural styles muddled my sense of past and present.

These feelings of anxiety were quickly assuaged as I entered the City Hall area. Perhaps it was the French Renaissance-inspired architecture that made me feel more calm, or the general muted color palette of the buildings, or the large park near City Hall, or even the sinking bedrock below my feet that forced buildings to shrink in size. Either way, the atmosphere of this area pulled me in and made me not want to leave. I wandered around City Hall Park in the quiet shade of the blooming trees and admired the new spring flowers swaying gently in the breeze.

The polished back entrance of City Hall features beautiful arched windows and giant trees that frame its entrance. In the background of this image, there is a small corner of a skyscraper visible, however, I felt as though I was in a sanctuary completely separate from the chaos I had just left. As I sat in the park and admired its peacefulness, I could not bear to bring myself to leave. I had some idea of the chaos that would ensue as I edged closer to Fourteenth Street, and I did not want to subject myself to that kind of overstimulation. Perhaps part of my connection to this area stemmed from, as Self would put it, how my interior self is aggravated by my exterior environment. The City Hall area reminds me of the Boston Public Gardens, an area where I have spent a lot of time, as it is so close to home. My appreciation for this park and the buildings surrounding it may be rooted in my longing for home and a general nostalgia for days spent in the Boston Public Gardens with friends who I have not seen in a long time. Nevertheless, at long last, I continued to walk up Broadway.

As I had not yet reached Canal Street, I was still in the midst of the Bedrock Valley, and thus the buildings had shrunk considerably from the ones in the Wall Street area. Despite my belief that the sense of peace I felt at City Hall would stick with me throughout the Bedrock Valley, I soon felt the same sense of uneasiness creeping back. It almost felt as if there was too much space—as the buildings shrunk, the area around me felt cold and empty, filled only by uneven concrete sidewalks and stone facades of buildings. It was quite empty in terms of people, and I only encountered four or five people in my path in this area. The road also felt wide, but perhaps this was due to the fact that there was no construction taking up an entire lane of traffic, as was often the case near Wall Street.

The photograph I took at the corner of Broadway and White Street depicts the eerie sense of wide-open spaces in that neighborhood. In contrast to the Financial District, where the sky was scarcely visible, the sky in this image takes up almost half of the frame. Furthermore, the roadway is less chaotic here than it had been further downtown, due to the availability of all lanes. Additionally, the architecture of each building appears to be in conversation with the rest—each building has some sort of arched window and a decorative cornice at the top of the building to tie them all together. Despite the eerie feeling given by too much space, I did appreciate the cohesiveness of the architecture. It made it easier for me to walk up Broadway without being distracted by every little detail on every building. I could easily admire the intricate stonework on the buildings without being blinded by a neighboring glass skyscraper. I think my overall impression of this area was indifference: I didn’t want to be there if I didn’t have to because of the strange sense of space and the awkward feeling of being in some sort of abandoned ghost town, however, I would much rather have been in this area than near Battery Park.

At this point in my journey, I was feeling quite worn out. I had been walking for roughly thirty minutes, the sun was shining, and the only thing in my stomach was iced coffee. And yet I trudged on, reaching the SoHo area. Although the buildings stayed around the same height as the ones before Canal Street, there were a few buildings that dared to grow taller, and this number increased as I walked north. The streets also felt more full. Because this area is largely filled with retail shops, I encountered many young people on Friday shopping sprees. Perhaps because I am more familiar with this area or perhaps because it seemed like the perfect combination of building height, crowd levels, traffic, and street noise, I felt most comfortable in this area of my walk. There seemed to be a recipe for how to create a comfortable walking environment—the buildings must be six to seven stories tall, there must be considerable crowds of local people, not businessmen from the suburbs and tourists, and there must be traffic, but not so much that the noise reaches an unbearable level. However, as I continued up Broadway, this equilibrium fell out of balance once again.

The area between SoHo and Union Square is interesting in that the buildings are tall and there are people walking about, yet the purpose of the area seems in disarray. There were families, students, commuters, and young kids all walking about. Additionally, the businesses felt out of place in this area—while the buildings in SoHo were obviously for retail and residential purposes, there were buildings associated with New York University, residential buildings, McDonald’s, T-Mobiles, and FootLockers. It felt like an out-of-place suburban strip mall. Furthermore, the constant construction and scattered scaffolding had returned to the scene, creating a din that was absent earlier in my walk. Although I was increasingly becoming annoyed with the chaos of the building usage and the growing level of street noise, I plowed on.

Finally, I had reached Fourteenth Street after an hour and a half of meandering. Union Square Park seemed a fitting place to end my journey, as I had begun at Battery Park. Both parks provided nice viewing areas of the city and the heights of the buildings around me. As I stared out across the park to the many streets that lay ahead of me uptown, I was again struck by the grandness and sheer mass of the city. This area certainly felt the most “New York” to me: I could hear the subway underneath me for the first time on my walk; I could see street performers and artists sprawled along the sidewalk; the buildings, although quite tall, felt typical of the New York skyline; and the constant stream of honks faded to background noise. Again, I felt a sense of comfort in this area because of how expected it was. I could expect there to be street noise, I could expect the buildings to tower over me, and I could expect the crowds associated with the Fourteenth Street subway station. With this sense of agreement between land and mind, I concluded my journey at 14th Street and headed home to write up my observations.

Analysis

How did my walking experience relate to my understanding of the geology along the path I walked? Before I started my research, I held the belief that in areas where the bedrock is closer to the surface and thus more skyscrapers were present, I would feel more anxious. I attributed this anxiety to the height of the buildings, the number of people I expected to be in the area because of the greater amount of space as created by taller buildings, and because of the amount of traffic that denser areas generate. As I began my journey in Battery Park, I proved my hypothesis to be true. The dissolution of time and space as created by the varying architectural styles and various monuments engendered an anxiety in me that I was unfamiliar with in the city. I believe that the bedrock being closer to the surface of the Earth provided a versatile canvas for builders to build upon, thus producing a variety of buildings. Furthermore, the amount of construction and street noise added to the unrest I felt. The nature of the geology in this area and the proximity of bedrock to the surface I believe fueled my sense of uneasiness and anxiety. Because of the sturdiness of the land, taller buildings could be built, thus creating a denser urban space that I was not used to experiencing. Furthermore, the density as created by the skyscrapers caused more people to be in this area, thus creating strange and unreadable crowds. Tourists, businessmen, and people of all ages seemed to be in this area for reasons I could not seem to understand. Finally, as the geology allowed for more buildings to be created, I felt the least connected with nature on this part of my journey. The area of the sky visible to me was quite small compared to other areas, and anything green seemed to be overtaken by urban sprawl. The air felt dense and thick because of the construction, and the trees and shrubbery peppered the sidewalk felt artificial.

As I moved up Broadway and into the City Hall area, I noted how this anxiety melted away. As mentioned earlier, City Hall marks the start of the Bedrock Valley, where the bedrock dips up to 150 feet below the surface.15 This shift in geology and its effects on my mood was noticeable. I moved through the space with ease, I noted how much calmer I felt in this area. Although the shift in architecture from forty-story buildings to four-story buildings had not widely occurred, as illustrated by the skyscraper looming behind City Hall in my photograph, the green space and architectural uniformity helped me to feel at ease. Although the psychogeography of this landscape had its hold on me and kept me sitting in the park for longer than necessary, I am not sure how much of that can be attributed to geology. As illustrated by Pincus’s cross-section of Broadway, the drop in bedrock is gradual, and this is why I only begin to feel the effects of deeper bedrock as I get closer to Canal Street.

As I meandered through the Bedrock Valley, the feelings described in my notes do not seem to align with my hypothesis. I had speculated that the Bedrock Valley would generate shorter buildings, which was true, but I also theorized that I would feel more at ease in the areas of shorter buildings because of the visibility of the sky, connectivity to nature, and lower density. In reality, while I did note the lower density of the area before Canal Street, it did not give me the calm feelings I thought, but rather feelings of uneasiness and isolation. The wide roads, vast sidewalks, and low buildings coupled with the fact that I encountered few people left me feeling strangely lonely. Although the bustle below City Hall left me feeling anxious, I also was a bit entertained and excited by the chaos. There was always somewhere to look or someone to see. Near Canal Street, however, things were much less exciting. I wanted to quickly escape that area and thus did not meander or take the time to stop and admire the architecture. While the architecture of these buildings was much more aesthetically pleasing and easier to comprehend due to their uniformity, I wanted to escape the isolated and unnerving feeling that the area was giving me.

I did not expect to feel so comfortable upon reaching SoHo. Perhaps I only felt comfortable in contrast to the isolation I experienced before Canal street. Nonetheless, the uniform architecture comfortably sized crowds of young shoppers, and the flowing stream of traffic made me feel more at ease than the wide empty streets below me. The nature of this area of Broadway was predictable and easy to understand, and thus it was easier for me to feel comfortable. Although the Bedrock Valley was shrinking, the hard stone was not yet completely close to the surface, and thus this area was not as full of skyscrapers as the area near Battery Park. Although there were a few skyscrapers, a large amount of sky was still visible to me, and thus I was able to feel like I had more breathing space.

This sense of comfort followed me to Fourteenth Street despite the growing height of buildings. Although there was an area of uneasiness before Fourteenth Street caused by the unpredictability of the buildings and wide range of groups of people, once I reached Union Square Park, I was able to feel freed from the clutches of the chaotic and unpredictable urban sprawl. The presence of the park completely obliterated my hypothesis. As the Bedrock Valley shrunk to nothing as I walked to fourteenth Street, I expected to feel the ensuing urban chaos that I had felt so deeply near Battery Park. However, I had not anticipated the calmness I would feel. The fields of Union Square Park and lush trees broke up the towering skyline, and thus instead of looking onward to menacing buildings, my line of sight was interrupted by urban greenspace. The park gave me considerable distance from the urban chaos that lay ahead, and instead of feeling anxious, I felt calm. This differed from my experience of Battery Park. At the beginning of my journey, I stood in Battery Park and looked out at the entirety of the city, awestruck by its sheer mass and density. I felt these same feelings at Union Square Park, however, here my journey ended whereas at Battery Park I had to endure the dense urban sprawl I was looking upon. Nevertheless, my psychgeological walk from Battery Park to Fourteenth Street up Broadway helped me to gain firsthand experience of how the layout of urban spaces can shift with the geology underneath it. As I walked along, I was constantly thinking about the rocks underneath my feet and how they were informing what I was seeing before me, and this heightened sense of awareness inspired a greater appreciation for Manhattan’s geology as well as how the city was built. Even though some of my theories about how I would experience the various levels of bedrock happened to be proved incorrect, my fieldwork still helped me to gain firsthand knowledge of the shifts in architecture and building density that occurred between Battery Park and Fourteenth Street.

Conclusion

In using a psychogeographical approach to understand the effect the geology was having on Manhattan’s urban sprawl, I was able to gain a better understanding of how the land underneath us can uniquely inform how we move through the city. By documenting my experiences in psychogeological analysis, I hope to provide the groundwork for my future research on this subject. Although this project solely focused on my experiences with the urban environment, there is room for further research by documenting how others interact with the land around them. Using a geological lens in an ethnographic style project, I believe there is much to be discovered about how different demographics move through the urban environment. Furthermore, it could be valuable to explore not only how the varying depths of bedrock affect an urban landscape, but also how the specific characteristics of the underlying rock inform the urban environment. As documented in my geologic map of Manhattan, the East Village area is composed of gneiss and marble. These rocks are completely different from the Manhattan schist that I looked at in this project, and thus it could be interesting to examine the effects of these types of rocks and compare them to my current research. Although I was not able to go into depth on the fieldwork that I conducted in that area, I hope to use it in future analysis.

Overall, my findings concluded that there is a correlation between Manhattan’s geology and the layout and ambiance of the urban environment. While my findings are limited as I only surveyed a specific area and used my own perceptions as the basis of my analysis, I found that the buildings varied greatly at differing bedrock depths and this gave each urban space a completely different atmosphere. Certain areas had the power to make me feel anxious, excited, comfortable, nostalgic, or indifferent, and it is important to recognize that while these feelings were engendered by the urban environment I was experiencing firsthand, the geological layout underneath that environment is largely what was informing my experiences. The architecture near Battery Park completely differed from the SoHo area architecture because of the depth to bedrock, and thus the ambiance of each area inspired different feelings. We must not forget or invalidate what is underneath our feet as we walk through the city, no matter how insignificant it may seem or how many feet below us it is. Although the rocks that makeup Manhattan were formed millions of years ago, they are still greatly affecting our everyday lives. Placing a deeper value on the power of the Earth’s movements and how they have shaped our present-day experiences will engender a deeper understanding of our cities’ pasts and help us to think more clearly about their futures.

- MiaHull, Mia Hull, “Rock Scrambling and Bedrock: A Geohistory of Manhattan,” GeoHistories: Co-Evolution of Earth and Life, October 22, 2016.

- Hull, “Rock Scrambling and Bedrock.”

- JasonBarr, Troy Tassier, and Rossen Trendafilov, “Depth to Bedrock and the Formation of the Manhattan Skyline, 1890-1915,” The Journal of Economic History 71, no. 4 (2011), 1062.

- Barr et al., “Depth to Bedrock and the Formation of the Manhattan Skyline, 1890-1915,” 1062.

- Barr et al., “Depth to Bedrock and the Formation of the Manhattan Skyline, 1890-1915,” 1060.

- Barr et al.,“Depth to Bedrock and the Formation of the Manhattan Skyline, 1890-1915,” 1061.

- Barr et al., “Depth to Bedrock and the Formation of the Manhattan Skyline, 1890-1915,” 1072.

- Guy Debord, “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,” Situationist International Anthology, revised and expanded edition, edited and translated by Ken Knabb (Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 39.

- Debord, “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,” 10.

- WillSelf and Ralph Steadman, Psychogeography: Disentangling the Modern Conundrum of Psyche and Place (Bloomsbury, 2007), 60.

- Debord, “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,” 10.

- KennethBrophy, “Urban Prehistoric Enclosures,” Empty Spaces: Perspectives on Emptiness in Modern History, edited by Courtney J. Campbell, Allegra Giovine, and Jennifer Keating, 190.

- Brophy, “Urban Prehistoric Enclosures,” 185.

- Debord, “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,” 10.

- Barr et al., “Depth to Bedrock and the Formation of the Manhattan Skyline, 1890-1915,” 1062.