How does the convenience of music streaming inform our respective music tastes? And why is this alarming for both artists and fans? A meditation on how streaming influences our tastes in music, featuring songs by Prince, Ryo Kawasaki, Erykah Badu & Portishead.

Music Streaming & Monopolizing “Taste”

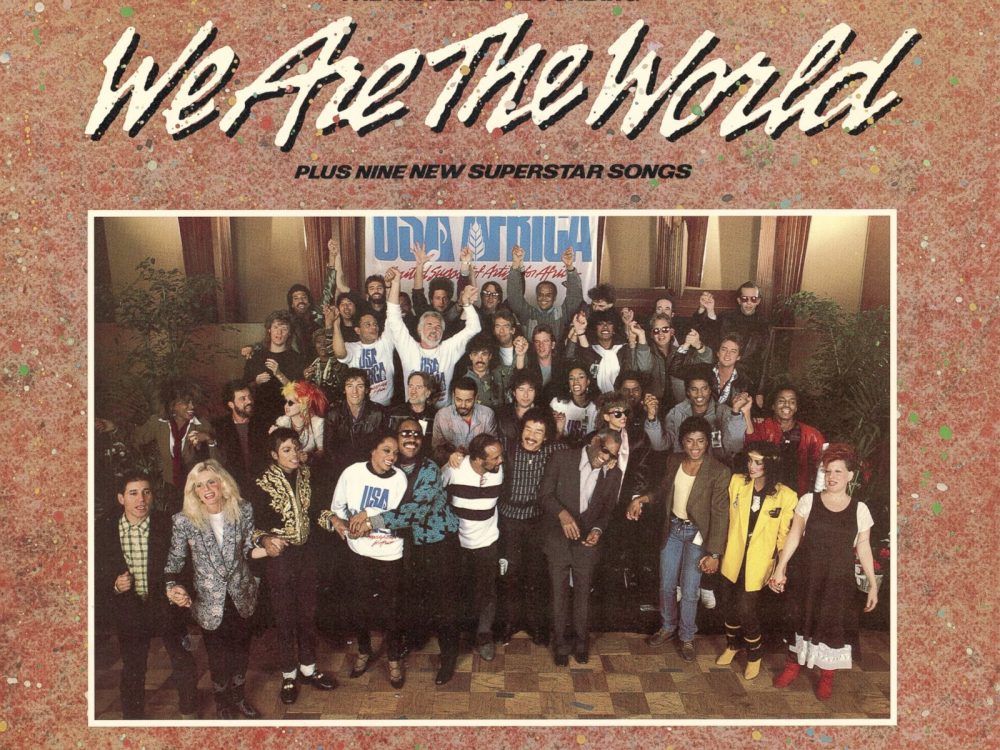

In Nolan Gasser’s LA Times Op-Ed: “Music is supposed to unify us. Is the streaming revolution fragmenting us instead?”, the ex-Pandora Radio co-architect laments the consequences music streaming has had on the music industry. He poses the question, “Is our musical isolation playing a contributing role in the broader fragmentation of society?”, a bold, vague and, potentially even sensationalist claim.1 What’s more probing than his question is the title of his article—Music is supposed to unify us. Is it? No one can deny that “music” as an audio(visual) medium has always informed cultural, and potentially even greater societal unity within any given society with musical traditions. As far as the United States is concerned, however, traditional American folk musics have slowly been overshadowed by a behemoth popular music industry over the course of the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries—creating a different sense of cultural unity altogether. Thus, the music industry, particularly as it concerns the American popular music industry, is a different conversation entirely. Sure, USA for Africa’s 1985 hit “We Are the World” was undoubtedly a unifying moment for music lovers across the country, but the song didn’t exist solely to support African development, nor was it necessarily a “unifying” force for the Africans who were the subject of the record. What’s even more curious is that there wasn’t a single African artist featured in a song dedicated to their entire continent.

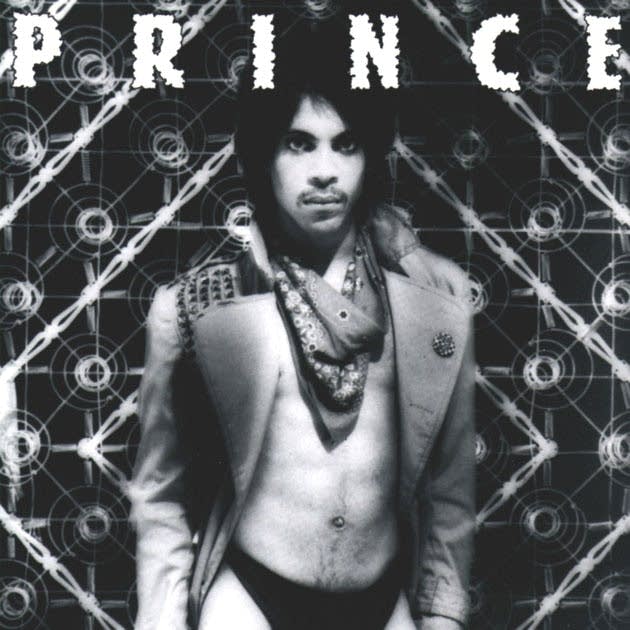

One of the recent examples of societal unification through music Gasser cites is our universal mourning of Prince and the “collective swaying to ‘Purple Rain.” Interesting that he uses Prince as an example…Not the Prince who continued to push the boundaries of sensitive societal norms regarding race, sex, gender, definitely not the Prince that rebelled against record label heavyweight Warner Bros. by adopting the unpronounceable “Love Symbol” as his moniker, appearing in public and performing with the world SLAVE on his forehead, and later saying “I became merely a pawn used to produce more money for Warner Bros.”2 Prince stirred controversy every year of his time as an artist in the American music industry—he wasn’t exactly a proprietor of societal unity in America, except for maybe those who enjoyed his music (which naturally, will decline as new generations emerge and establish their own styles and tastes) and felt inclined to mourn his death. But of course, if you release an album called Dirty Mind with songs called “Head” and “Sister” in 1980, you’re bound to make some enemies. The most ironic part about Gasser’s use of Prince’s death as a unifying moment in America’s music history, is the fact that Prince, while he may have not agreed with Gasser’s reasoning, would have agreed with the sentiment—he wasn’t exactly a supporter of music streaming. In July 2015, he withdrew his music from all streaming platforms to sign an exclusivity deal with Tidal, favoring the Black-owned, artist-run service over platforms like Spotify and Apple Music.3 Not just Gasser and Prince, but many artists ranging from Thom Yorke to Beyoncé have expressed disillusionment with streaming platforms, specifically Spotify. Whatever the reason, Prince(‘s estate), Yorke, and Beyoncé, among many others, despite their opinions on streaming, will reap the benefits that come with visibility/ accessibility on music streaming platforms and the increasingly omnipresent playlists which heavily influence the tastes of everyone from the casual music listener to the avid fan.

Music streaming, if anything, was supposed to be more of a solution to a problem than a problem in and of itself. The dominant mode of music consumption outside of purchasing physical music prior to streaming was radio. Mainstream radio, unfortunately, has always been an entity which more often than not, only offers a sliver of the full spectrum of popular music available due to constraints over what music can and cannot not be played. Mainstream radio bureaucracy aside, there did exist alternatives like college/independent radio stations, local shows, and specialty record stores. Still, there did not exist a way to listen to music quite like music streaming—a single platform where millions of songs could be immediately accessed at any time or place was unfathomable unless you worked at a radio station or record label, or simply invested large sums of money into physical music copies and audio hardware.

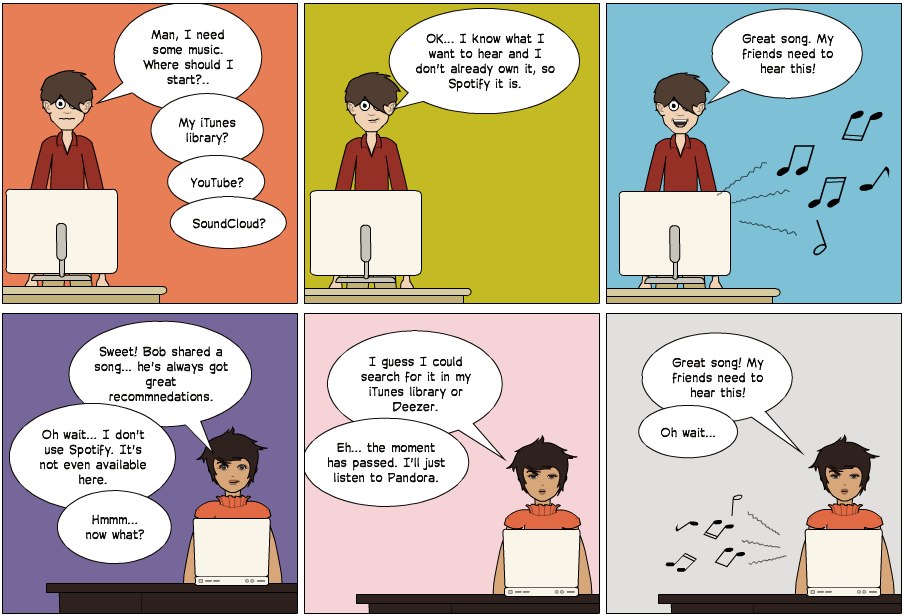

Music streaming has certainly democratized music listening at large since its onset, but we must remember that streaming, like past modes of music consumption, does have its limitations. “Black” and “white” music are increasingly becoming distinctions which bear no resemblance to our contemporary musical reality, due in part to the sheer accessibility of music in the present-day. There exists people of all races, ethnicities, and nationalities within essentially every genre or style of popular music, excluding those which concern more obscure, traditional folk styles. Furthermore, instead of having to leave one’s home to buy a physical copy of music—prone to misplacement or damage—everyone’s music can exist comfortably in the “cloud,” and can be accessed within seconds by the click of a button. Streaming services even take what you listen to and curate playlists based on your music tastes, but also create their own playlists for you to listen to if you’re feeling too lazy to look for music yourself. Talk about convenience! Now everyone can interact on their respective platform, share the music that’s available, and feel unified in their allegiance to whatever music streaming site they choose to use. What’s the point of going through the hassle of buying music or converting a YouTube link to MP3 if streaming exists? Why search for music when a meticulously curated playlist is always available? Is there anything wrong with a service that eliminates the burdens and inconveniences that hindered music listening in the past? What if these services are making it music listening too convenient?

Currently, Spotify stands as the most popular music streaming platform with 170 million total users, but Apple Music actually has more songs available, clocking in at 45 million to Spotify’s 35 million. Of the “Big Three” music platforms, however, it’s Tidal that has most music available to its users with over 50 million songs available.4 Despite these high counts, what if I told you these numbers weren’t even close to the total number of songs ever recorded and available for consumption? It may seem nitpicky to question or even criticize streaming platforms that appear to be doing the best they can to include as much music as possible within their respective databases. However, when these platforms also inform what music has the potential to become popular, and what artists can actually reap the benefits of music streaming, the conversation becomes much more complicated. While streaming services are supplying a convenient alternative to past modes of music consumption, they are also creating a monopoly on music taste—what music gets curated and consumed, and what music does not.

According to Rolling Stone, services like Apple Music and Spotify have about 50 percent of their artists hailing from North America—49.7 percent for Apple Music and 48.5 percent from the United States alone for Spotify. The U.K. follows behind with around 12 percent for both services, while South America as a whole accounts for 11.7 percent of Spotify’s artists—Apple Music isn’t mentioned in this case.5 That being said, entire continents are also left out of this discussion, specifically Asia and Africa. Now, iTunes, in conjunction with Apple Music, does allow you to download any music from the internet directly into your iTunes library, meaning I can make up for the lack of African and Asian visibility on streaming platforms. However, despite each of these platforms advertising—to varying degrees—the ability to share music with friends and family within each interface, iTunes does not show music I’ve downloaded from the internet to people who follow me. Furthermore, no single streaming platform has a built-in mechanism for sharing music across platforms. There is essentially no built-in interactivity between music streaming services.

One album you might find on Spotify may not be available on Apple Music, while an album that’s available on Tidal may not be available on any of the other platforms. Some music isn’t featured on any streaming service, with the exception of YouTube. Then there’s music that you must scour the depths of the internet to find on a blog from 2007 that hasn’t been moderated in almost a decade, or can only be found on exclusive websites and obscure music sharing platforms, if they can be found online at all. It isn’t necessarily surprising that streaming platforms grant North American artists greater visibility, but that doesn’t make this decision any fairer for fans, and especially not for artists.

For music fans, what are the implications behind an entity having so much influence—power even—over what we listen to? There’s something strange about living in a world where practically anything can be accessed through the click of a mouse, and yet, while each respective music streaming service promotes inclusivity and gives off the impression of having “all” the music one could want, they only have a fraction of the music available on the internet, and even smaller fraction of all the music which has been made for popular consumption. Should streaming platforms have as much influence over how music gets to us as they do control over what music will unify us?

This “monopoly of taste” could be remedied by some kind of mechanism for inter-streaming sharing, if it weren’t for the fact that these mechanisms—texting, emailing, in-person sharing—already exist. There is a certain convenience inherent in music streaming that plays a larger role in our collective hesitation towards stepping outside of our musical comfort zones as far as streaming is concerned. This is due in part to the user-friendly nature of music streaming and the carefully curated digital libraries we’ve accumulated, respectively. Why download music to iTunes if I’m so used to Spotify? Why would I consider what music Tidal has if I’m already satisfied with Apple Music’s selection? Questions like these are compounded by the combined presence and convenience of the aforementioned curated playlists, which have had an increasingly significant influence on which artists receive popularity, what music gets listened to, and the general music tastes of everyone from the casual listener to the music junkie. As an artist that exists outside not only streaming itself, but also the culture borne out of streaming, that artist has to work many times harder to make themselves known to an audience that does not “see” them, and thus does not hear them.

Lets circle back to African and Asian artists who occupy the outskirts of the music streaming industry. Last spring I interviewed Japanese jazz guitarist Ryo Kawasaki for my radio show on WNYU, Newtype. Among the many things we discussed were the negative implications inherent for certain artists who must keep up with the pace of the music industry in order to support themselves. As a jazz musician, especially at the age of seventy-two, he cannot put music out with the same speed at say, an electronic music producer or hip-hop artist can. As he gets older, it will take more time, effort, and money to record, release, and distribute music. Yet, despite his age, he already has an extensive library of music—thirty releases since 1970 and 130 album credits (instrumental performance, writing and arrangement, production, etc.) in total.6

Only thirteen of his albums are on Apple Music and Spotify, and two of them are compilations. Tidal has eight of his albums, two of which are also compilations. Music from his band Tarika Blue is available on all three platforms, but it isn’t exactly common knowledge that he was a core member and co-founder of the group, and even if it was, it’s not like Kawasaki or any of the other band’s members would see significant financial gain as a result. Unfortunately for music listeners, Kawasaki’s most creative, genre-bending, groundbreaking, and forward thinking music is absent from these platforms, most of the albums available being easy listening smooth jazz and solo guitar music. For Kawasaki, however, there are very tangible consequences behind his lack of visibility on streaming services. A few months ago the prolific guitarist who has performed with the likes of B.B. King, George Benson, and Elvin Jones had a gofundme started on his behalf, as he had been struggling to keep up with his rent payments and needed money to pay outstanding bills. Erykah Badu, who sampled Tarika Blue’s “Dreamflower” for her 1999 song “Didn’t Cha Know,” has seen a steady flow of money since her music arrived on streaming services, while Kawasaki doesn’t even receive royalties from the song because of an expiration clause for sampling.

Thom Yorke of Radiohead and Geoff Barrow of Portishead especially, can sympathize with Kawasaki’s situation. An article from NME documents a Twitter thread initially started by Barrow that was later retweeted by Yorke, where the former expresses his disillusionment with music streaming and Spotify as an entity, specifically as they concern paying artists. In a response to Barrow’s question of how many musicians have “personally made more than 500 pounds ($648 USD) from @Spotify”, songwriter Daniel Broadley replies that Spotify can be a good earner if that artist in question makes music easily commodifiable for the platform’s genre specific playlists. But is it fair to force artists to compromise their respective styles based off of their viability for appearing on these playlists? Barrow doesn’t think so. He laments the current relationship between artists and streaming, commenting on how for bands that aren’t genre-specific—Portishead being one of those very bands—”it’s almost impossible to make a living.”7 Like Portishead, Kawasaki and other artists, musicians, and bands who have either dedicated their careers to blurring genre in favor of unhinged creative freedom, or simply work within the inherently ‘anti-genre’ Fusion subgenre, you can’t really count on Spotify playlists to give you any meaningful visibility if it is indeed true that releasing genre-specific music can help remedy income issues. This will almost definitely become an issue if said artist isn’t North American in origin, and not working within whatever genres are most popular during the time. So, if you’re a Japanese jazz musician like Ryo Kawasaki who hasn’t seen a creative or financial peak since the nineties, it’s no surprise that you won’t be as susceptible to reaping the benefits of Spotify playlists. If Portishead, an established group since their album debut in 1994, is having trouble seeing income through Spotify, imagine how hard it is for so many artists who have their music available on the service.

Streaming isn’t just detrimental to artists who do not have music on curated playlists, but can be extremely counterproductive for artists who aren’t on Spotify specifically—the most popular streaming platform. In this era where streaming platforms compete with each other over streaming market shares, each respective platform comes with their own set of incentives to subscribe, further complicating the conversation surrounding streaming as an entity that mystifies whether or not we truly have the freedom to choose what we want to listen to. While Apple Music and Tidal offer incentives that might be inconsequential to the average music listener (i.e. high fidelity streaming on Tidal and the ability to download music into your iTunes library and have it exist alongside your Apple Music library), Spotify offers free Hulu with premium subscriptions, giving prospective streamers even more of a reason to close themselves off from the musical possibilities outside of streaming—why would anyone in their right mind use Tidal or Apple Music, and to an even greater extent, even think about going through the trouble of downloading music into iTunes or listening to music on YouTube at all when Spotify gives you a better deal ($4.99 a month in comparison to Apple Music and Tidal’s $9.99/mo deal) AND free TV. Suddenly it feels like I’m forced to choose between cheap music and free TV bundle, and my own freedom to listen to and watch whatever I choose, but also support the artists that I choose—even if I don’t necessarily have to make a single decision. If I opt out of streaming altogether I can take back my music listening preferences into my own hands and curate my own “taste”, though in the process I’ll be cutting off one of the only ways I can directly pay an artist outside of physically buying their music or seeing them perform live. While listening to vinyl and CDs are fun, I’m not buying a portable CD player anytime soon. If an artist doesn’t have their music on streaming at all, their only option is to source most of their money from touring, a costly and exhaustive route that can burn out any artist or band if it’s their only source of income. Music streaming, thus, is not only a conversation about monopolizing taste while giving music listeners the impression of “choice”, but how this monopolization stands as a direct obstacle to artist’s financial compensation.

When looking back at the Gasser article, it’s interesting to see one of the very architects of the music streaming industry bemoan its success. Pandora hasn’t exactly fared well since the inception of Spotify, Apple Music, and Tidal, but Pandora was certainly never at the forefront of featuring new, obscure, or unknown artists. Even more interesting is how the concept of radio—the antithesis to streaming, the former heavily curating, almost controlling one’s access to music choice, and the latter giving the false impression of “choice,” while still controlling one’s tastes on a much smaller, less slightly less significant, yet insidious scale—laid the foundation for the initial wave of music streaming platforms. Pandora, though a “radio station,” is actually not wholly unlike the music streaming manifestations of today, the platform essentially being an automatic “playlist” that plays certain music based off what was played prior—it just doesn’t show you what’s going to be played before it gets played. It wouldn’t be crazy to say Gasser, alongside his Pandora co-architects, actually pioneered the current manifestation of music streaming, and thus, the monopoly of taste which has proved detrimental to both artists and fans alike.

- Nolan Gasser, “Music is supposed to unify us. Is the streaming revolution fragmenting us instead?” Los Angeles Times, June 16, 2019. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-gasser-music-unifying-20190616-story.html

- Jessica Lussenhop, “Why did Prince change his name to. a symbol?” BBC, April 22, 2016. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-36107590

- Daniel Keeps, “Roc Nation, Prince Estate Clash Over Singer’s Digital Catalog.” Rolling Stone, November 14, 2016. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/roc-nation-prince-estate-clash-over-singers-digital-catalog-104863/

- Hugh McIntyre, “The Top 10 Streaming Music Services By Number of Users.” Forbes, May 25, 2018. https://www.forbes.com/sites/hughmcintyre/2018/05/25/the-top-10-streaming-music-services-by-number-of-users/#3b974bdf5178

- Emily Blake. “Study: Music Streaming Is a Global Business—But Its Playlists Still Favor U.S. Music.” Rolling Stone, September 27, 2019. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/streaming-playlists-spotify-apple-music-891342/

- Ryo Kawasaki. Discogs. https://www.discogs.com/artist/136140-Ryo-Kawasaki

- Nick Levine. “Radiohead’s Thom Yorke still isn’t a fan of Spotify.” NME, December 29, 2017.https://www.nme.com/news/music/radioheads-thom-yorke-shares-spotify-concerns-2196648