“I have felt within Venezuela throughout my entire life while spending all of my twenty outside of it. In an attempt to finally understand what happened to the beautiful country in my mother’s stories, I begin to ask questions and start memorizing her recipes.”

Crisis and Cooking

Maternal Love as a Radical Practice of Reclamation

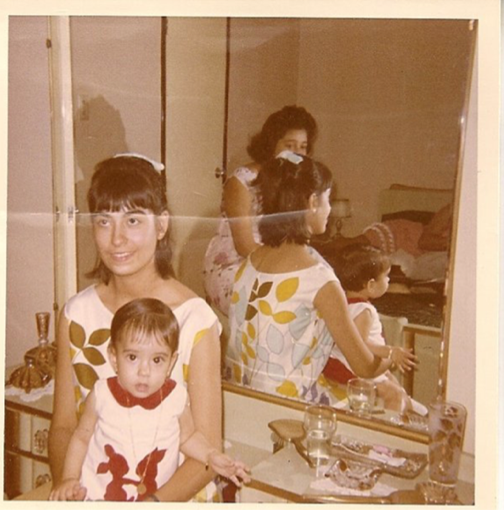

Sitting at the kitchen counter, I watch my mother make pan de jamón in the late hours of the night into the morning. The dough has been rising in the warm oven all day, under the protection of one of her favorite dish towels. She sprinkles flour over the granite and throws the dough out of the bowl. She massages flour onto the rolling pin and begins her hardest work: kneading and rolling. I’ve never noticed my mother’s muscles before this moment, but there they are, probably growing stronger from each time she prepares this family dish. She tries to talk, to make casual conversation as she rocks back and forth pushing the dough out, but her sentences are interrupted with her heavy breathing and grunts—she’s getting older, I can tell. That’s why I watch now, so that I can one day undertake this workout, too, and keep making the Venezuelan food I’ve eaten throughout my childhood.

Since my birth, in 1998, I’ve been a part of the Venezuelan diaspora. Though I was not always aware of my belonging to this group, or even knew where Venezuela was, the cultural practices my mother instilled in my siblings and me always communicated that we were not like all of our American friends. From eating arepas and empanadas with weird cheeses at school, to speaking Spanish at home, my upbringing was quintessentially Venezuelan. But at ten years old, I grew increasingly aware of how far Venezuela really was. I started to notice the shift in the room when someone wanted to bring up politics from home, and I watched my Vovo1 cower over his portable radio listening to reports of violence. Though I didn’t speak Spanish anymore, I could pick up on the sadness in my mother’s voice and heard the fatigue in her sighs between conversations. And two new stepfamilies, both moving from Venezuela in 2010, fresh with information about the crisis and its worsening state made this distance seem larger, farther, more impossible to cross.

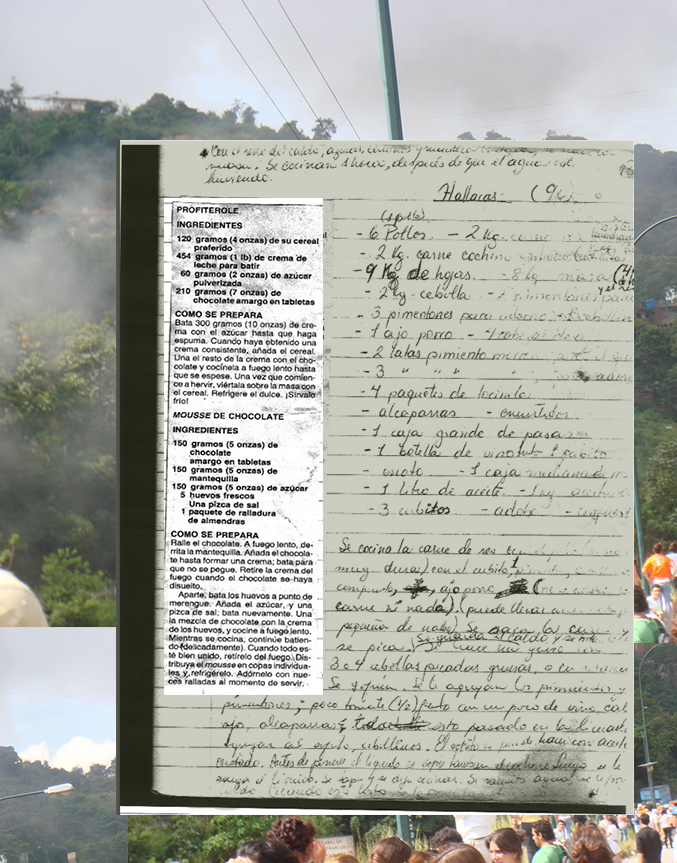

At present, I still straddle this line: I have felt within Venezuela throughout my entire life while spending all of my twenty outside of it. My interest in the worsening political climate is therefore a given, a natural result of caring for my relatives and family members so deeply affected by the never-ending stream of catastrophe. In an attempt to finally understand what happened to the beautiful country in my mother’s stories, I begin to ask questions and start memorizing her recipes. With little food left in her home country, my mamita is always in the kitchen, making the arepas and hallacas, now suddenly absent there. As she undertakes these domestic traditions, she divulges her experiences immigrating to America and being physically distanced from a crisis so close to her heart. She tells me her story over pliable arepa dough, the chopping of onions, and the tasting of different cheeses.

My parents, Carlos Schuler and Nathalie da Costa Ferro first left Venezuela in 1987, travelling to the Bay Area in California where my father had been offered a grant to conduct his PhD research at the University of California, Berkeley. “It felt lonely,” my mother tells me. “We came in January and . . . there was nobody from Venezuela here.” It had always been my parents intention to move back to South America. They wanted to start their family back home and show their children around all the neighborhoods of Caracas, so putting down roots in the United Sates was never a major priority. Three years later in 1990, when my brother, Alejandro, was born, my parents were less alone, but they also grew less certain of their path back home. In 1992, an attempted coup d’état led by Hugo Chávez began a new era of increased militarism and violence in Venezuela, one to which my parents were not eager to return. “We saw tanks approaching Miraflores,2” my mother says. “We looked at each other, and at Alejandro playing nearby, and said ‘that’s no place to raise him. We are not going back.’”

In the years following, my parents only grew more sure of their choice. In 1999, Hugo Chávez was elected into presidency under a socialist campaign that promised to save the Venezuelan economy. Until 2013, Chávez ruled in Venezuela with policies that attempted to repurpose government money for social programs. But, most of these policies incidentally relied on the Petróleos de Venezuela (PVDSA), a state-run oil monopoly. Venezuela was headed for financial crisis as early as 2002, causing inflation to rise and the country’s people to suffer. This tension was then compounded by the rising totalitarian policies that restricted freedom of speech. Some individuals were even threatened by Chávez’s supporters for publicly contradicting the government. Fearing their lives, their security, and the future of the country, many others began to flee Venezuela. And fearing bloodshed, violence, and state militarism, my parents had to accept that their kids would never visit the Venezuela of their childhood, and seeing tragic news reportings on the television was probably the closest we’d ever get.

In these early years, my parents were completely isolated from Venezuela. “Contact with home meant calling our parents about every two weeks for ten minutes,” my mom says. “The rest was done via letters. I would write on the outside of the envelope: ‘This letter has no drugs, just pictures of my home and family. Please deliver it to my mom so she knows I’m okay.’” Apart from these exchanges, which were few and far between, my parents lived cut off from daily life in Venezuela: “it was a total separation. It’s not the same now. Instagram, Facebook, all of those things keep people together.” With the internet becoming more accessible in the late ’90s, my parents became able to visit their home country in a way migrants had never could before: through social media, photos, and viral videos.

However, looking at images people being savagely beaten, my mother and father felt their Venezuela was lost, not re-found. Their beautiful city landscape and waterfalls were gone, replaced by poverty, pain and hunger. “It adds to the . . . stress of those of us who are outside. We can call for free, know who had a baby, but at the same time, we also know what’s going on,” my mother explains to me. Rather than feeling closer to Venezuela through these online connections, she feels a greater distance, as she is unable to recognize her changing country. “The country we left no longer really exists,” my father says, also explaining this dissonance. For him, “Venezuela is this distant land, existing only in memory, like a dream to which [he] can never return.” Because most of his friends and family have also migrated and the physical landscape of the country itself has changed, returning to Venezuela would not mean returning “home” for my father. That home remains in the past with the memories of the people and family he knew, and he has tried to create a new one, here in the United States.

But finding a new home can be tricky, especially when the crisis back home rages on. Though my mother feels lucky to live here, the more bad publicity she sees about Venezuela, ironically, I think the more she feels a desire to go back. Regarding the phenomenon of being tied to home through media updates, my mother says: “It makes it much harder to integrate into the new culture. Look at my dad—he’s always hooked on something, on the web, he knows who the governors are, he knows everything going on. If the government fell and the country went back, I think my dad would go back. He’s here . . . but he’s there.”

I wonder where my mother is on those nights she stays up cooking, sacrificing sleep for culture, here or Venezuela? On the warm summer days of my childhood when we would sit at the beach and eat empanadas, is it possible she dreamed we were in Caracas? How did she find herself at home living so many miles away?

In 2010, my mom remarried her third-grade sweetheart and is currently housing his mother, sister and niece, who left Venezuela this past year. Surrounded by Venezuelan culture, she said that she felt closely connected to her home, checking news postings and sharing articles to her Facebook page daily. Speaking about the loss of the beautiful sights she recognized as her country, she says, “Everything changed. But you know where Venezuela is,” she looks around the room, where her family is baking classic Venezuelan recipes, “It’s here. It’s in the cake she’s making, in the music we listen to, in the food you’re eating.” For my mother, home seems to be defined by continuing traditions and customs that the current residents of Venezuela can no longer carry on: “People in Venezuela don’t have the money to make these things anymore—they can’t buy ham, or harina pan, or salt even. So who makes it? The diaspora. Venezuela is when we all get together. We took the country in pieces and took it to different parts of the world, and when we come together the country reassembles itself in kitchens.” For my mother, a ‘homecoming’ of sorts is achieved when we take part in these traditions despite being miles and miles away from Venezuela. She hinges her notions of home on passed down culture and people. I think back to the many nights I’ve spent watching her make that pan de jamón.

After stretching the elastic dough out onto the full width of the counter, she drinks some water, and melts the butter in the microwave. Like a painter, she begins to brush the beautiful gold butter over the pale dough, giving it a greasy glean. Everything is done with a gentle touch, and her bread becomes a work of art. She sprinkles over raisins, not leaving a white spot in sight, lays the olives in a straight vertical line down the center, covers them over with bacon, and lays the ham on thick. “You miss the food,” she whispers after a few moments, and that’s all she needs to say. I understand. Not only is this bread love, it is a radical act of reclamation and resistance against the erasure of her identity. As her role in the family would seem to be heavily based on emotional support, calling upon her traditional knowledge of recipes, language, and religion, it is harder for her to envision an idea of home separate from Venezuelan practices. Perhaps in some strange way, she even feels more enamored with her country since having left it, since seeing the destruction and loss of these practices for those still there.

Currently, Venezuela stands in a period of decay. After Chávez’s death in 2013, Nicolás Maduro inherited the country, and drove it further into the ground. In order to maintain patronage, Maduro began printing money, starting the country on a path that led them to the current inflation rate of 1,000,000 percent3. More than this, hunger and malnutrition are becoming a leading cause of death for young children as medicine and hospitals lose funding, access to medication, and bed space. The fraudulent re-election of Maduro in 2018 dashed any hope of reconstruction left in those still remaining, and a mass exodus of more than 2.7 million people (about 9 percent of the population) began.4 No groceries left on the shelves, no teachers in classrooms, riots in the streets, and a countrywide blackout—Venezuela is no longer a place built for humans to survive.

My mother says this knowledge makes her feel “impotent . . . desperate,” she goes on before falling silent for a few minutes, “and sad,” she finishes, choking back tears. Knowing she can’t return home, she clings to her Venezuelanness in the best way she knows how—through cooking. The government can only take so much—the groceries, the electricity, the money—but not her identity. “It’s really hard to know what my country used to be and see what it is now. Why did we allow it to happen?” she asks. “Why did we get comfy and destroyed by politics?” These last few questions hit hard for me. Though I’ve never been to Venezuela myself, I, too, have seen the physical change of the country in photos and through my parents’ stories. And living in the United States, I witnessed the smooth transition from Obama to Trump, and I live surrounded by neo-Nazis and neoliberals. Like my mom, I fear power, I fear politics, and I fear its potential to destroy. Caught up in my uncertainty and fright, like a child, I just want to hug my mamita and help her finish cooking.

Everything I know about Venezuela is filtered through the memories of my family members, is tainted and influenced by their perspectives. Carrying the knowledge of my siblings, my parents, my grandparents, alongside seeing the brutal news reports and media postings, my image of Venezuela is ultimately confused. I long for justice in Venezuela for the sake of my mom, of my stepsister, and most of my family members plagued by guilt and sadness, while still claiming that these held traditions are enough to help me understand where I’m from. Relearning Spanish, listening to gaitas, cooking traditional meals and passing them on, this is how we try to build and hold on to home.

“One day you will go to South America,” my dad says to me, “and it will make sense in a wonderful way.” I’m not sure how far away this day is. But, I remain hopeful for its arrival, and I continue to stand in solidarity with my people miles away, continue to make pan de jamón with my mom. As she rolls the bread into a perfect spiral, I notice the deep care she has for this dish. The meal is her baby. She caresses it, pokes and prods at it the same way she used to do when she braided my hair or straightened my clothes. My eyes grow heavy, and my mother asks if she can fry me some cheese. Her entire existence is love. This bread is love. Love for me, yes, but also love for her country to which she cannot return. As she lives out her life in America, denied the ability to visit her streets, she cooks Venezuelan dishes, in the hopes that she can reignite the Venezuelan consciousness and instill it in her children. I shake my head and say I’m not hungry. I head off to bed, knowing she’ll be up for hours—waiting for her perfect bun to come out of the oven. I drift asleep, and I can still hear the Venezuelan cowboy music lightly playing in the kitchen. As the cuatros delicately trill, I begin to dream of freedom for my mom, my family, for me, for Venezuelans, for the world.

¡Larga vida a Venezuela libre y soberana!

- My grandfather is originally from Portugal, so we use this pet name for grandpa.

- The Venezuelan equivalent of the White House

- Jorge Luis Pérez Valery and Abdel Alvarado, “Venezuela Gives a Rare Look at Its Economy,” CNN Español, May 29, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/05/29/economy/venezuela-inflation-intl/index.html.

- Rocio Cara Labrador, “The Venezuelan Exodus,” Council on Foreign Relations, July 8, 2019, https://www.cfr.org/article/venezuelan-exodus.