Interpretability allows stories to transcend the barriers of space, time, and context.

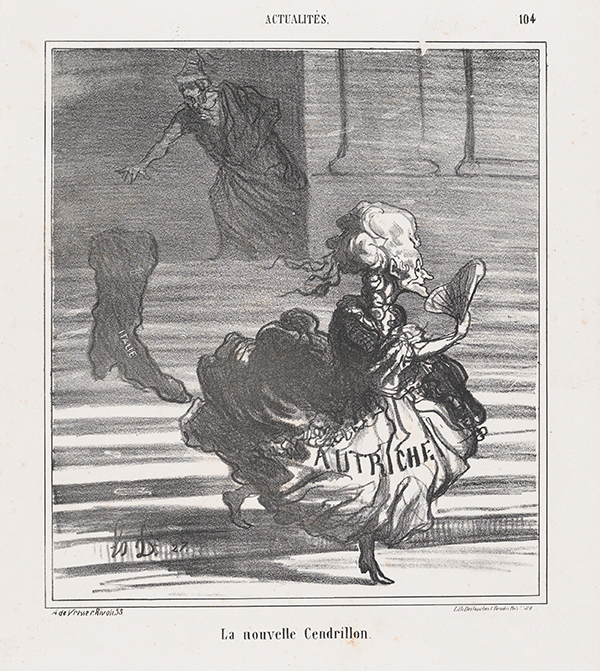

Another Cinderella Story

Some narratives’ unique ability to elude a precise interpretation allows them to persist in the public imagination. The difficulty in establishing a concrete meaning behind the story lends power to the narrative, which perhaps testifies to why select stories persevere over time. Unable to decipher a concrete meaning behind a story, readers interpret a text in a way that suits their predispositions. Interpretability allows stories to transcend the barriers of space, time, and context. The Bible proves one such example of a text that remains relevant in contemporary discourses because one may pinpoint a moral in the text’s stories based on predispositions, potentially exclusive from the authors’ intent. Texts which leave themselves open to interpretation invite readers to engage more actively with the text than those which define exactly what the reader should take away from their reading. The fairy tale “Cinderella,” collected and edited by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, an adaptation itself, exemplifies how ambiguous narratives persist in contemporary discourses precisely because the story’s ability to shirk off precise interpretations and beget a multiplicity of meanings, specifically as a narrative of either class liberation or female oppression.

The Grimm Brothers’ “Cinderella” follows an orphan girl who must live with her abusive stepmother and two stepsisters. Cinderella, the orphan, not only receives no luxuries in life but also must wait on her stepfamily. However, Cinderella defeats her stepsisters in accruing favor with a local prince, gaining victory and happiness in marriage. One may interpret depending on the aspects on which they choose to focus. To a certain degree, “Cinderella” depicts a peasant’s ability to transcend class barriers. On the other hand, Cinderella must compete with the other women in the land for her mobility, which only comes though marriage, that is, at the patriarchal authority’s acquiescence. Two interpretations emerge which appear to contradict each other; one represents an escape from class-based suffering whereas the other reinforces a narrative the suppresses female agency and orients a woman’s success in relation to a husband. This paper deems the class mobility interpretation the “liberatory reading” and the female competition interpretation the “oppressive reading.” These terms themselves rest upon a specific approach to reading Cinderella, attesting to how one’s perspectives and experiences shape their interpretations. Each reading possesses its own evidentiary footing, but also stands open to further interpretability.

With the liberatory reading, Cinderella proves the protagonist and her stepfamily the story’s villains. Referring to Cinderella, whose father recently passed away, the stepmother inquires, “What’s this terrible and useless thing doing in our rooms?”1 The stepmother continues on to say, “off with you to the kitchen . . . whoever wants to eat bread must first earn it . . . she can be our maid”2 Cinderella, without a kinship network to rely on, must engage in domestic labor to sustain herself in life. The Grimm Brothers published “Cinderella” in 1812, and Cinderella’s contemporary plight as a nineteenth-century child without parents or wealth leaves her vulnerable to her caretaker’s exploitation. Without her wealthy father to defend her, Cinderella falls prey to the Georgian era labor-wage system that only weakly distinguished children from adults. The stepmother’s rhetoric enforces this idea in that Cinderella confers little use to the family if not through her work. Her exploitation shines through in that not only must she work to earn her keep, but she must labor in the service of the wealthy if she hopes to survive. This echoes a capitalist ethic in that the wage laborer garners payment insofar as their employer reaps a surplus value from their production.

Cinderella’s name emphasizes the significance this story attaches to the liberatory reading. The Grimm Brothers clarify that for Cinderella “there was no bed . . . and she had to lie next to the hearth in the ashes” and “since she always rummaged in dust and looked dirty, they named her Cinderella.”3 Even the protagonist’s name situates her at the bottom of the ladder and associates her beginning with filth. Every time that someone refers to Cinderella, the speaker reminds her about the circumstances of her reality, enhancing the power that her stepfamily yields over her. Furthermore, the stepfamily applies this name to Cinderella, which enunciates the degree of agency that Cinderella possesses in her current situation. Moreover, the reader only knows Cinderella by the name granted by her oppressors, which may ultimately shew what one takes away from the story. Those the details which the narrative presents or eschews provide a backbone upon which one fabricates their interpretation. This exemplifies the power the editors wield in shaping how one perceives a story or its adaptations. The rich hold the naming rights in the story, and Cinderella seems to lack the capacity to consent in the narrative. Nevertheless, Cinderella does try to find ways to subvert her stepsisters’ demands in their absence.

With her sisters attending a ball at the kingdom’s palace , Cinderella “climbed to the top of the ladder of the pigeon coop and could see the ballroom [. . . ] indeed, she could see [. . . ] a thousand chandeliers glittered and glistened before her eyes.”4 Though Cinderella remains under her family’s command in their presence, in her solitude, she shirks off her labor. In doing so, she reclaims her time as her own and hurts her abusers who benefit from her exploitation. On top of this, Cinderella gazes upon the forbidden realm of wealth denied to her. Through her voyeurism, Cinderella declares herself someone capable of capturing others in her sight and objectifying them in her imagination. Taking in the view of the castle and its chandeliers, Cinderella acquires the ability to imagine herself outside her immediate class position. Through access to a world unknown, Cinderella gains an understanding of her class position and the world that exists just beyond her reach in the distance. However, this world of wealth remains just that, far away in the distance. The pigeon coop bestows on Cinderella a viewing station, but she must further accumulate materials that will enable her easy access into the fields of opulence.

Scheming to attend the dance, Cinderella cries out, “But how can I go there in my dirty clothes.”5 Cinderella recognizes her own state of raggedness, which highlights the prevalence of others’ normative criteria in shaping one’s worldview. Even the poor in this story gaze upon themselves through a distorted lens that privileges the cleanliness and finery exclusive to the upper classes. Cinderella eventually wishes upon the magic tree at her mother’s grave, which provides her with “pearls, silk stockings, silver slippers, and everything else that belonged to her outfit.”6 To stand with the elite, Cinderella first must commit herself to performing wealth and disguising those attributes that disclose her social station. The Grimm Brothers evince how Cinderella may access a happily ever after only if she engages in those socially manifested archetypes to which the rich in the story subscribe. With her polished appearance, Cinderella forces herself into the running for a better life outside poverty and inevitably exhibits the ability to transcend one’s class status.

This liberatory reading hinges on those aspects of “Cinderella” that demonstrate the degrading conditions that Cinderella faces in poverty and casts a positive light on her marriage to the prince at the story’s end. To read “Cinderella” this way relies not only on using this particular evidence which relates to transcending class barriers, but also to read the facts the story presents through a particular filter. One’s beliefs about how classism operates, one’s notions concerning class inequality, and one’s attitudes toward aristocracy largely influence whether or not a reader views the story’s message in a positive light. For example, one may interpret Cinderella’s name to convey a different meaning, in that she embodies a phoenix who will rise from the ashes. One may also posit that her name denotes a fiery spirit, which represents her inner power and chaotic energy that will usurp her oppressor’s position, and that this passion emanates from her position in the dust. Even such attempts to destabilize the liberatory reading may be interpreted in a way to further buttress her engagement to the prince as an ascent. Interpretations depend on the information that the text submits, as well as how the reader processes this knowledge upon their own individual reading. Herein lies the problem, in that people may maneuver unchanging texts through their interpretations in the way that suits the particular readers’ class biases and political aims.

One may argue that a nineteenth-century fairy tale’s various interpretations may not hold relevance in contemporary debates concerning classist liberation or female oppression. However, in 1950, Walt Disney Studios released an animated motion picture based on the Grimm Brother’s “Cinderella.” In terms of box office, the film boasts a total $263,591,415 worldwide from all releases to date, with around nearly $85 million of that sum coming from domestic patrons.7 Perhaps Disney’s motivation to create the film lies in its noticeable success with releasing the film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), but one should also consider the time period in which this particular fairy tale reached the silver screen. In his article “Fifty Years of Family Change: From Consensus to Complexity,” Frank Furstenberg argues that the 1950s contain perhaps the greatest’s degree of “traditional” family values in the United States. Though any point in history reveals non-traditional families, Furstenberg claims that in the 1950s, “the median age of marriage fell to just over twenty years for girls” and that “marriage at this time constituted [. . .] the transition to adulthood.”8

Considering this information, the sexual and gender culture of the 1950s is reflected in the film which depicts a female heroine whose only opportunity to escape her family’s home pivots on a male savior and ends with her betrothal to the knight in shining armor. This underscores the extent to which historical and social context either enhances or diminishes a narrative’s ability to attain popularity. The period in which the Cinderella story, and its adaptations, resurfaces speaks to how stories with great interpretability may continually serve its contemporary editors’ purposes and moral attitudes. A key point lies in deciphering what “readings” or underpinnings an adaptation places at the story’s forefront. With the original Grimm adaptation, written amidst a time facing class turmoil and strict gender politics, one may apply either the liberatory or oppressive reading to the story at arrive at separate conclusions with relative ease. However, the 1950s film, influenced by the existing culture, appears to attach more emphasis on those details which enable the oppressive reading, or one which idealizes marriage. Applying the both liberatory and oppressive readings to “Cinderella” underscores the potential problem with packaging this story into the Disney version geared toward child audiences and this modified narrative’s impact on young viewers.

Disney’s film adaptation does little to alter the elements which lend weight to the liberatory reading. Much of Cinderella’s socioeconomic status carries over from the original fairy tale into the film. However, the film adaptation does alter Cinderella’s living conditions quite a bit. The first few moments in the film pan upwards to a lofty tower on top the stepfamily’s estate. Cinderella wakes up in the tower’s concealed attic on her own bed and then rushes to perform her chores in song and dance with the help of singing animals.9

In elevating Cinderella’s lodgings, Disney hinders one’s ability to arrive at the liberatory reading. Cinderella bears her name only because of the ashes on which she must sleep at the command of her bourgeois family. In glamourizing Cinderella’s living conditions and her labor, the film takes away from a reading that shows a servant rebelling against her oppressors. Whereas in the fairy tale Cinderella seems to recognize her drudgery, Disney’s version paints the picture of someone complacent and cheerful in their reality. One might assume that Disney wishes to direct audiences to the oppressive reading, funneling attention towards the heroine’s marriage plot. Also, Disney’s veiling of poverty in the film perhaps indicates a pandering to their potential audiences. The children watching the 1950 version were likely not poor orphans living in miserly conditions, but American children whose parents could afford a movie ticket. In modifying the portrayal of Cinderella’s servitude, Disney moves to limit the reading of class anomaly to favor a tale that American children may better latch onto. This demonstrates the ways in which stories may be picked apart and adapted to the lessons the story communicates, which likely match the beliefs of those in control of the narrative.

The oppressive reading of the Cinderella tale and its subsequently lucrative film adaptation assists in highlighting how one may interpret this story to buttress patriarchal notions concerning the family and women’s position in society. To start, both the fairy tale and the film position woman against woman in the competition for the prince’s hand in marriage. In the Grimms’ version, one stepsister informs Cinderella that the “prince, who’s the most handsome in the world, led us onto the dance floor, and one of us will become his bride.”10 Later on, the stepsister hears that Cinderella stole a glance at the ball from the pigeon coop, and “filled with rage . . . she immediately ordered the pigeon coop to be torn down.”11 Enmity and jealousy plague the stepsister’s interaction with the beautiful Cinderella. The narrative partakes in an ideology that not only values female beauty in the marriage market but affirms the greater “purchasing power” that eligible bachelors carry into the search for a spouse. In the end, only one maiden may garner the privilege to catch the male’s eye and secure their future. Moreover, one may interpret this jealousy to arise out of the stepsister’s fear that she may not find a mate and remain a spinster, utter doom for a woman in the early 1800s.

The original “Cinderella” further confirms the oppressive reading in the moment that Cinderella flees the prince’s party at midnight. In the Grimm Brothers’ version, the prince “had the [exit] stairs painted with pitch black so that [Cinderella] wouldn’t be able to run so fast.”12 Though the fairy tale describes three separate royal parties whereas the Disney film version only includes one party, and so the prince lacks the foresight to set a trap, the animated adaption nevertheless portrays the royal guard dramatically pursuing Cinderella.13 Each telling reifies the narrative of a traditional courtship model, in which the male performs the hunting and may employ tricks to catch his prey. The painting of the palace steps exemplifies this reading in that the hunter sets a trap with the explicit aim to hinder the prey’s mobility. In the film version, the entire royal guard follows the prince at the royal authority decrees, intimating the power backing patriarchal hegemony. One may interpret Cinderella’s attempt to flee occurring in both versions an act of agency on her part, but one should also remember that at midnight Cinderella loses the luxury items that cause her to sparkle in the prince’s eyes. That Cinderella fears being seen without her finery buttresses the idea that the story adheres to a repressive reading in that female worth only goes so far as the beauty she exhibits within the context of the male gaze.

Perhaps the most startling aspect of the Cinderella fairy tale, and its greatest divergence from the 1950 film, arises from the stepsisters’ acts of self-mutilation in the attempt to fit into Cinderella’s slipper. In the Grimms’ telling, One stepsister whose “foot was too large [. . .] bit her lips and cut off a large part of her toes.”14 The impetus to fulfill the prince’s requirements echo women’s historical struggle to secure herself through marriage. Though the stepsister fails to deceive the prince, the story illuminates just the extremes that a woman with few prospects may undergo in altering her body to satisfy a potential suitor. One considers the extent to which this idea holds relevance with perpetual innovations in elective cosmetic surgeries, and who exactly defines the ideal body type. Furthermore, the emphasis on the dainty foot in relation to the ideal women brings to mind foot-binding practices and the female body’s feminization in the male sexual fantasy.

This evidence adds legitimacy to the oppressive reading of the Cinderella story told in the fairy tale, and leaves one contemplating how this impacts the similar, albeit distorted and euphemistic, Disney portrayal. Though the film leaves out the body mutilation, the stepsisters continue to fight over a man, mistreat their fellow woman, and take extreme measures to contort their bodies into the glass slipper’s mold. Disney hides away the horror but keeps those things about Cinderella tale which truly fortify the oppressive reading. One ought to contemplate the role that epoch plays in the production and consumption of popular narratives in the media. Both versions emerge in times in which this particular narrative may hold relevance to those audiences consuming the finalized product. Both the early 1800s and the 1950s appear times in which narratives about class or female mobility through marriage appeal to the imaginations of the contemporary viewing parties. One period with the Industrial Revolution and the other with a postwar boom; both were times in which people may dream about experiencing rapid wealth accumulation to save them from their drudgery. With the oppressive reading, both periods appear times where women may imagine that marriage is the pathway to liberation from their parents’ homes. Regardless of the interpretation, one notices a potential link between contemporary culture and the narratives that those cultures engender.

The Cinderella narrative demonstrates the power that the reader holds in interpreting a story. One may choose the liberatory reading, the oppressive reading, or any reading that they may conjure. Cinderella might depict a triumph over classism or may embody a severely anti-feminist argument about female agency. Readers cannot know an author’s intention, and that hardly matters once the reader processes the text on their own. The reader themselves falls prey to the cultural machinations of their lifetime which structure how they perceive knowledge and narratives. The stark contrast between the liberatory and oppressive reading, as well their own susceptibility to reworking, conveys the danger that the fungibility of interpretations poses in political debates. Cinderella is simultaneously a an aberration in class rigidity and an angel in the house.

- Jacob Grimm et. al., “Cinderella,” The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition (Princeton University Press, 2014), 69.

- Grimm, “Cinderella,” 69.

- Grimm, “Cinderella,” 70.

- Grimm, Cinderella, 71.

- Grimm, “Cinderella,” 71.

- Grimm, “Cinderella,” 72.

- “Cinderella (1950) – Financial Information,” The Numbers, accessed March 1, 2020.

- Frank Furstenberg, “Fifty Years of Family Change: From Consensus to Complexity,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 654, no. 1 (July 2014):15.

- Cinderella, Directed by Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson, and Hamilton Luske, Performances by Ilene Woods, Eleanor Audley, and Verna Felton (The Walt Disney Studios, 1950).

- Grimm, “Cinderella,” 71.

- Grimm, “Cinderella,” 71.

- Grimm, “Cinderlla, 73.

- Cinderella (1950).

- Grimm, “Cinderella,” 75.