The similarities between the tourist industry today and settler presence in the Caribbean are striking: Both thrive on the idea that the Caribbean is a place that can (and should) be freely consumed, economically and visually, by Western people.

(De)(Re)Naturalizing the Caribbean

Picture this: it’s a balmy 27°C (80°F), the breeze coming off the sparkling blue ocean is lightly caressing your body where you lay, splayed out in the sand, cocktail in one hand and book in the other. You are one of the few people on the beach, and aside from the rhythmic crash of the rolling waves, the only sound that enters your consciousness are the noises of the lush forest just behind you. You think about waving over the man dressed in a linen uniform that is serving orange juice to a couple closer to the water. You want to ask him to bring you some fresh papaya picked from the trees in the orchard behind the beach hotel in which you have rented an ocean-view suite, but there is not a cloud in the sky and the sun rays are beating down on you; maybe you wait until after you have taken a dip in the cool sea water. Where are you? On a luxurious Caribbean getaway, of course.

When we think of the Caribbean we think of empty, untouched beaches, of tropical fruit, extravagant cocktails, beach-side hotels, easy living, “island time,” and indulging ourselves; we think of escaping to luxury. While the Caribbean has long been associated with vacation and pleasure in the imaginary of the Global North, the sordid and violent history of displacement and slavery on the Islands is left widely unmentioned in mainstream media. The region has played a central role in Western history; these were the shores that Columbus stumbled upon before he arrived in the present-day United States, and it is not a coincidence that the transatlantic slave trade coincided nearly perfectly with the enlightenment period in Europe. As Frantz Fanon writes in Wretched of the Earth, “European opulence is literally a scandal for it was built on the backs of slaves, it fed on the blood of slaves, and it owes its very existence to the soil and subsoil of the underdeveloped world.”1 How is it then, that the Caribbean has been “spatially and temporally eviscerated from the imaginary geographies of ‘Western Modernity’”?2 How is it that we still conceive of the Caribbean as a getaway paradise, whose history and current events are of little import to daily life in the metropole, to which people (who have the means to do so) can escape from the daily struggles of reality?

(De)(Re)-Naturalizing the Caribbean is a theoretical exhibit, imagined for the purpose of exploring larger questions about the role of collective memory in the present day. How does the Caribbean’s colonial history effect the politics and perception of the region today? By revisiting colonial constructions of the Caribbean, can we alter the hierarchical perceptions (and behavior) of the Global North? The exhibit examines, through colonial art production, how the Caribbean has been consumed historically by the Global North, specifically in relation to its natural environment. The depiction of Caribbean ecology has played a pivotal role in the construction of the Islands as a place of luxurious escape. As Mimi Sheller points out in her book Consuming the Caribbean, “it could be argued that there is no ‘primal nature’ in the Caribbean both because so much of it has been constructed by human intervention,” referring to the introduction of exotic species and people and the extinction of indigenous vegetation and fauna, “and because every aspect of it is dosed with a heavy infusion of symbolic meaning and cultural allusions.”3 (De)(Re)-Naturalizing the Caribbean traces various historical moments in which European visual descriptions of Caribbean landscape have created certain tropes that continue to saturate present-day perceptions of the region. These depictions of the natural landscape serve as “starting point[s] for understanding the social relations of power that inform their [the Global North’s] relationship to Caribbean peoples.”4 The exhibit is split into three sections: 1) Discovery Period (Naturalizing), in which the colonial explorers and settlers first begin to record and visually represent the Caribbean landscape, 2) Scenic Economy (Denaturalizing), in which visual depictions of cultivated land were lauded over unwieldy natural vegetation in order to justify the slave trade and colonial presence, and 3) Post-Abolition Romantic Era (Renaturalizing), in which imagery of untouched, tropical fecundity returns in order to justify new modes of intervention. (De)(Re)Naturalizing the Caribbean highlights how the depiction of the Caribbean as an ahistorical paradise through pointed representation of its landscape silences both the past violence suffered on the Islands, the ramifications that said past has had on the contemporary reality of Caribbean people, and the asymmetrical power relations that constitute Western interaction with the Caribbean today.

Discovery Period (Naturalizing)

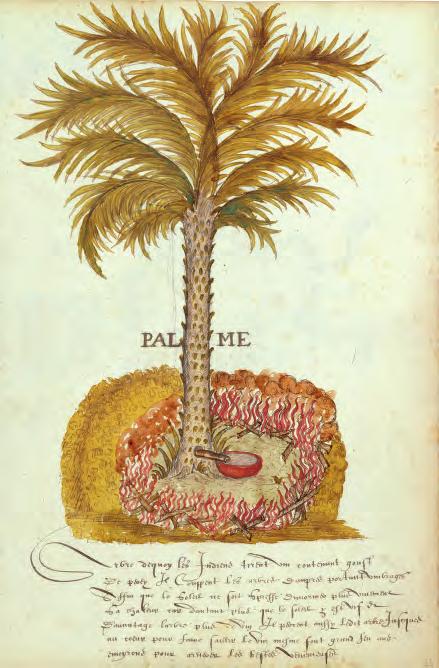

When Columbus and his entourage landed in the Caribbean in the 1400s, they were confronted with an ecological landscape that was completely unknown to them. The flora and fauna of the Islands were vastly different from the European landscape to which they were accustomed , so they were compelled to find new means of survival. While the settlers attempted to bring with them a variety of European crops such as wheat and olives, none of these crops were suited for the tropical climate.5The settlers were therefore heavily dependent on the indigenous people’s knowledge about plants and hunting for survival. The settlers began to acquire this knowledge (most likely through forms of enslavement) and record it in visual manuscripts that acted as manuals for new colonizers.6 The image above is taken from the Drake Manuscripts, an extensive catalog of Caribbean vegetation created by Francis Drake, who sailed to the New World with John Hawkins on the slaving voyages of 1567–1568. The Drake Manuscripts contain close to two hundred watercolor images of West Indian plants and animals. The example here depicts a palm tree and displays visual tropes typical of the other images found in the manuscripts. The tree is taken out of context (isolated from its natural background), which emphasizes its form and makes it easier for readers to recognize. Importantly, it also displays imagery and description of how the plant was cultivated—by clearing the surrounding trees, building a fire around the base, and tapping the trunk for palm juice. The palm tree was of vast interest to the pioneers, as it could be utilized for a multitude of purposes. This included the harvesting of palm wine, which was especially attractive to the settlers. 7

The Drake Manuscripts, and other similar visual accounts of the Caribbean, not only served as a kind of instruction manual but also informed “an imagery of tropical fecundity and excessive fruitfulness, which conjured up utopian fantasies of sustenance without labor, even though this was manifestly at odds with the difficult experience of survival.”8 This “tropical fecundity,” also depicted in the literature of the settlers of the time, tied the Caribbean to images of the garden of Eden and the medieval fantasy of the Land of Cockaigne, an imaginary land where all of life’s pleasures (namely, food, alcohol, and sex) were abundant and available, an illusion not too far off media depiction of the Caribbean today.9,10 Representing the Caribbean in this way served as a useful propaganda tool for the colonizers as it helped them secure financial backing from rich sponsors in the metropole as well as convince potential settlers and indentured servants to make the journey to the Islands.11

Additionally, in cataloging the Caribbean plants (and bringing many of these plants back to the metropole) the settlers were one of the earliest exercisers of imperial acquisition. Ordering and collecting plants envisioned the tropics as a place where materials could be collected and systematized, a notion that plays an important role in the next section of the exhibit.

Scenic Economy (Denaturalizing)

The drawing displayed here, Canna de Zucchero (Sugarcane), appeared in the colonial publication Il Gazzeteire Americano in 1763, and depicts an idyllic scene of a Caribbean plantation. The artist shows an ordered plantation and uses garden-like imagery (such as the neatly sectioned fields) to emphasize the planned aesthetic of the scene. Additionally, the perspective of the piece suggests that the scene is created from an elevated vantage point. This intimates that the scene is viewed through “imperial eyes,” as if the viewer is surveying their land.12 The huts lined up on the left of the image are meant to depict “negro huts” and give the impression of happy, peasant like workers.

Like most of the art and literature concerning the Caribbean in the eighteenth century, Canna de Zucchero is especially celebratory of the slave plantation, a quality that is indicative of a larger trend in the colonial imaginary of the time: the glorification of cultivated landscapes over the unwieldy natural vegetation of the Caribbean.13 Eighteenth century images propagated the idea that cultivation in the West Indies began with colonizers and enslavers, and lauded the productivity of cultivated land over the lush but “wasted” natural wilderness of the region.14 In conversation with travel writing of the time—much of which emphasized the terrifying and ugly wilderness of uncultivated areas—the images are implicitly anti-abolitionist, proposing that without European presence and the continuance of slavery, the land would slip back into savagery and ruin.15 The violence of slave labor is rarely depicted in visualizations and literature of this time; the ugly reality by which these plantations were built is completely absent. The colonial occupancy is thus painted as a necessary, pleasing, and welcomed presence, a belief used to legitimize further occupation. As Sheller points out, “the predominant theme in descriptions of the Caribbean remains the beauty of cultivated areas set within the tropical landscape. Uncultivated land could be declared ‘terra nullis’ and legitimately seized.”16

Interestingly, the palm tree played an important symbolic role in this era, too. The trees were often used as the markers at the boundaries of plantations, signifying where European control—and cultivated scenic “beauty”—ended, and the ugly, untamed wilderness began.17 The palm was also used as symbol of African-Caribbean struggle for freedom and independence, appearing on the National Seal of Haiti, the Haitian flag and currency, as well as being “a marker of emancipation in Jamaica and other islands.”18

Post-Abolition Romantic Era (Renaturalizing)

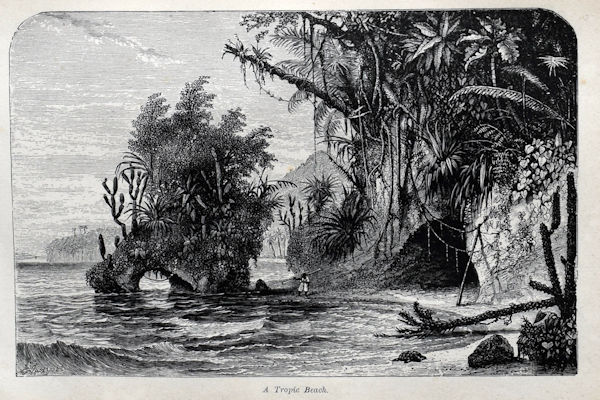

In the late nineteenth century, after slavery had officially been abolished, there was a clear move away from the depiction of plantations as picturesque in colonial art, a turn that can probably be attributed, in some part, to the abolitionist movement.19 Instead of orderly cultivation, we see the emergence of images that ‘renaturalize’ the scenery of the region, depicting lush, unruly forests and empty beaches. The depiction of the opulent wilderness of the Caribbean suggests that the islands are “virgin wilds,” untouched by man.20 Such depictions serve to erase the presence and the impact of the plantations, implying that their existence had hardly any ecological consequences. Reminiscent of the “discovery period,” the Caribbean is once again represented as an ever-replenishing Eden whose fecundity is limitless.21 Additionally, the art in this era was largely influenced by an emerging international appreciation of the sublime, defined as “taking pleasure in being overwhelmed by sights, sounds, sensations or ideas that are larger, greater, or more powerful than us.”22

These tropes can be seen in the drawing above, A Tropic Beach, taken from Charles Kingsley’s At Last: A Christmas in the West Indies, published in 1871. The book, one of many examples of travel writing in this era, was written and illustrated by Kingsley, an English clergyman, novelist and historian best known for his 1862 novel The Water Babies. It chronicles the author’s journey to the Caribbean in 1869. The vegetation in the scene that Kingsley depicts is clearly abundant and untamed. There is a single human figure who seems to be fishing in the lower half of the image; one tiny man in the midst of a sublime paradise. The text that accompanies this image in Kingsley’s book paints the author as an action hero that interprets the unchartered wilderness of the Caribbean for the reader, who assumes the position of an “armchair tourist.”23 At the time of the book’s publication, there was an upsurge in colonial literature telling of survival on deserted isles, Robinson Crusoe being one of the more popular examples. In this context, Kingsley depicts the Caribbean as a place for romantic escape and adventure travel. The image suggests that the region serves as an escape from industrial civilization, but also implies that the previously cultured land is descending into barbarism.24

Sheller writes that images of wilderness worked as pleas for a new European intervention: “post-emancipation decline of plantations in the old colonies was coded as the fall of civilization and regression into barbarism through the racist vision of lazy ‘darkies’ and unmanaged nature crowding in on once cultivated and productive colonies.”25 These kind of images implicitly voiced the need for Euro-American presence so that the abundant natural landscape could be utilized for more productive means. The propagated a belief that the newly freed slaves, and what was left of the indigenous populations, were incapable of using the land in a worthwhile way and needed outside assistance. Here the “White man’s burden” is evoked; it is the responsibility of the West to step in and help the Caribbean “develop.” This narrative served as a useful tool for American and European investors who took advantage of the Caribbean’s political and economic instability for their own monetary gain. The “natural” images of the Caribbean post-emancipation were used as a lure for economic “development,” military adventures, and forest fantasies.26

Similar to the imperial gaze evoked by images in the “scenic economy” section, the “armchair tourist” gaze that Kingsley invites in his work holds connotations of ownership. The book implies that the tourist is the first and only person who looks upon the virgin lands of the Caribbean. This often meant that under the tourist gaze, local life was turned into a consumable experience. The natives of the Caribbean become a part of the scenery; they are dehumanized and depicted as unchanging and backwards elements of the background.27

Furthermore, in this time, palm trees were ubiquitous in tourist brochures and adventure books. They were imbued with all the meanings that condense around the term ‘tropical’: escape, adventure, and romance. They signified the abundance of the islands, serving as a promise for all kinds of potential pleasures.

Deconstructing the Legacy of (De)(Re)naturalization

The historical legacy of Western visual culture depicting the natural landscape of the Caribbean is valuable to examine because it has played a central role in formulating the Caribbean in the Western imaginary today. Depictions of the untouched, fertile, and unwieldy ecology of the islands have survived centuries and perpetuate imperial civilizing discourse and notions of Western superiority. The similarities between the tourist industry today and settler presence in the Caribbean are striking: Both thrive on the idea that the Caribbean is a place that can (and should) be freely consumed, economically and visually, by Western people.

In his essay “Everyman His Own Historian,” published in 1935, Carl Becker writes about how the present is inextricable from the past: “Strictly speaking, the present doesn’t exist for us, or is at best no more than an infinitesimal point in time, gone before we can note it as present. Nevertheless, we must have a present; and so, we create one by robbing the past, by holding on to the most recent events and pretending that they all belong to our immediate perception.”28 Throughout Western contact with the Caribbean, meanings have been layered upon its natural landscape that continue to haunt our conception of it as an underdeveloped tropical paradise. Becker points out that “the specious present is an unstable pattern of thought, incessantly changing in response to our immdediate perceptions and purposes that arise therefrom. At any given moment each one of us . . . weaves into this unstable pattern such actual or artificial memories as may be necessary to orient us in our little world of endeavor.”29 The same structuring of historical narrative to suit particular goals can be applied to the construction of the imaginary Caribbean. Each section of the exhibition outlines how particular notions of the Caribbean landscape were highlighted in a given period in order to accomplish the colonial goals of the era. In the “discovery period,” the settlers “naturalized” the Caribbean by collecting and recording its vegetation and depicting it as an excessively fertile place in order to convince people in the metropole to invest or settle on the islands. In the period of “scenic economy” the landscape was “denaturalized” so that the organized aesthetics of slave plantation scenery were lauded above the unwieldy natural landscape in an effort to justify the continued use of slave labor. In the “post-abolition romantic period” the Caribbean landscape was “renaturalized” and once again depicted as lush and abundant in an effort to make the region seem an untouched paradise. The renaturalized images worked doubly to justify new types of Euro-American intervention as well as create the notion of the Caribbean as a location where adventure and romance abounds, the very qualities that attract tourists today. The aforementioned periods and their legacies continue to live on in the way that media portrays the Caribbean today: a getaway paradise where the stakes are low, and the living is easy.

If we do not look closely at the way in which visual culture has historically been used to manipulate our conceptions of the Caribbean, we will be unable to critically assess the part that the region plays in our contemporary imaginary, and therefore unable to address the asymmetrical power relations that hold the West as superior and justified in its exploitation. As Nietzsche warns, “as long as the past must be described as worthy of imitation, as capable of imitation and as possible a second time; it is in danger of becoming somewhat distorted, of being reinterpreted more favorable, and hence of approaching pure fiction.”30 This is clearly demonstrated in the “renaturalizing” of the Caribbean. The islands’ pre-Columbian ecologies cannot be imitated, as the effects of colonial presence and slavery have altered the environment irrevocably. Depicting the Caribbean as untouched, virginal wilds serves to silence the islands’ violent history and to perpetuate environmental and social destruction. Nature is thus continually exploited in ways that are unsustainable and destructive but also hidden under the guise of the ‘naturally’ abundant islands. As an example, Sheller points out that “while the hotel industry requires an endless supply of ‘pristine’ beaches, ‘untouched’ coves, and ‘emerald’ pools, any islands struggle with the water and sewage demands of the hotel industry, and sewage is returned to the same sea in which guests’ swim.”31 The idyllic image of the Caribbean that resorts project is a willful and damaging misremembering. Nietzsche goes on, “the past itself is damaged: entire large parts of it are forgotten, scorned, and washed away as if by a gray, unremitting tide, and only a few individual, embellished facts rise as islands above it.”32 The view of Caribbean ecology as “a kind of self-generating power that can be endlessly consumed and can withstand all that human consumption can impose on it,” has been created through the process of “renaturalizing” the islands. This removes any need for consumer guilt; if the Caribbean’s supply of tropical fecundity is endless, then there is no need to worry about the consequences of overindulgence. Nietzsche’s warning about history that approaches “pure fiction” is being enacted in real time; the Caribbean continues to be consumed by the West with dire consequences for both the environment and the local residents, and the West continues to dodge implication.

In “The Case For Reparations,” Ta-Nehisi Coates writes that “plunder in the past made plunder in the present efficient.” While Coates writes to advocate for reparations for African Americans, the same could be said of the colonial plunder of the Caribbean. As Coates puts it, “now we have half-stepped away from our long centuries of despoilment, promising, ‘Never again.’ But still we are haunted. It is as though we have run up a credit-card bill and, having pledged to charge no more, remain befuddled that the balance does not disappear. The effects of that balance interest accruing daily, are all around us.” The Caribbean is similarly haunted by the scars as a result of colonial presence. The palimpsest of constructed representations of the West Indian ecology continues to dictate the oppressive way in which the Global North interacts with the region, thus it is imperative to revisit and revise these relationships in order to imagine new ways of thinking about the Caribbean.33

- Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, translated by Richard Philcox (Cape Town: Kwela Books, 2017), 53.

- Mimi Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean: from Arawaks to Zombies (London and New York: Routledge, 2003), 1.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 36.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 1.

- That being said, the domestic livestock that the colonists brought with them thrived on the Islands and contributed massively to the extinction of local vegetation and animal life. Most likely they also played a large role in the extinction of the indigenous people of the region, whose means of sustenance they certainly encroached upon. The combination of this and the introduction of European disease decimated the local populations, who are almost completely absent from the Caribbean demographic today.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 39.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 40.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 42.

- In his several of his letters, Columbus referred to the Caribbean as “a veritable Cockaigne” (Sheller 42).

- . Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 42.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 49.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 50.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 50.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 50.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 48.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 50.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 66.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 54.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 53.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 55.

- “Sublime: The Pleasure of the Overwhelming,” Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2014, https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/calendar/sublime/.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 57.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 55.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 60.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 65.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 65.

- Carl Becker, “Everyman His Own Historian,” in Everyman His Own Historian (New York: Quadrangle Books, 1966), 226.

- Becker, “Everyman His Own Historian,” 227.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Use and Abuse of History, translated by Adrian Collins (Mineola: Dover Publications, 2019), 134.

- Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean, 68.

- Nietzsche, The Use and Abuse of History, 134.

- Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” The Atlantic, June 22, 2018, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/.