The wristwatch during wartime. An annotated history.

Rolex’s WW2 Consumers

Introduction

When Hans Wilsdorf started the Rolex watch company in London in 1905, wristwatches were widely considered effeminate baubles that men did not wear (Dennis, Dillon, & Stephens, n.d.). Only after experiencing the combat of World War I and recognizing the superior efficiency of a wristwatch over a pocket watch did men begin wearing these ‘feminine accessories.’ Recognizing how wristwatches had been appreciated for their functionality during wartime, Wilsdorf used the post-World War I period to build Rolex’s reputation aggressively around performance and technological innovation. David Liebeskind (2004), an adjunct professor of management at New York University’s Stern School of Business, explains, “in 1914, a Rolex watch was awarded a Class A precision certificate from the British Kew Observatory, an honor previously reserved exclusively for marine chronometers [and] in 1926, Hans Wilsdorf developed and patented the first truly water-resistant watch.”

Rolex’s emphasis on technology certainly paid off when World War II started, in that the pilots of the British Royal Air Force refused to wear the standard government-issue watches and instead bought the superior Rolexes with their own paychecks (Jones, 2011). Unfortunately, when many of these British pilots were shot down, enemy soldiers often seized the airmen’s Rolexes before imprisoning them. After receiving reports about these victimized clients, Wilsdorf responded by extending a generous and trusting offer to British prisoners of war: he offered these captives the opportunity to purchase a Rolex on a “buy-now-pay-whenever” purchase plan. Under this new corporate policy, which Wilsdorf handled personally, British prisoners of war could send a letter requesting a watch from Rolex’s Geneva headquarters, and receive a Rolex simply by giving their word to pay eventually.

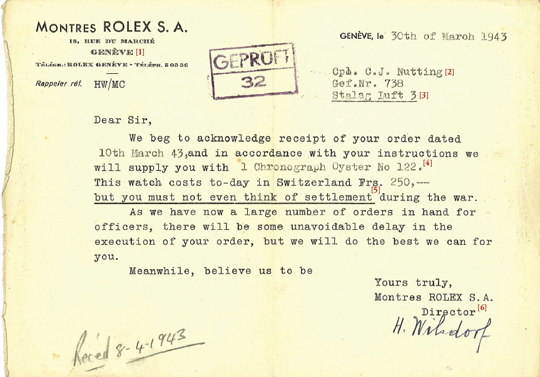

The confidence that Wilsdorf placed in British soldiers shows a seemingly selfless side to the Rolex Corporation. Financially, however, this practice of selling watches to prisoners of war proved to be a lucrative, and literally captive, market that the company could monopolize. This marriage of corporate morality and capitalistic scheming is plainly apparent in Rolex’s prisoner of war marketing motives, and even pervades the documentation of these World War II watch sales, as is showcased in this receipt of order that was sent to C.J. Nutting while he was imprisoned at StalagLuft III.

Historical Transcription of Receipt of Order

[1]

Genéve, or Geneva, Switzerland, is where Rolex relocated their headquarters in 1919 to escape England’s high import-export tax on the precious metals that the company used to make its watches (Stone, 2006). During World War II, however, Geneva proved to be a very limiting location for Rolex’s corporate headquarters because Switzerland was quickly encircled by Axis powers when Germany took control of Vichy, France (as early in the war as June 10,1940).

Although Switzerland was neutral throughout the war, being encircled by Axis powers greatly influenced the ‘neutrality’ of its international trade. This Axis encirclement, and the German counter-blockade that soon followed, prevented Swiss goods from reaching Allied powers, and therefore inhibited Rolex’s trade connection with the majority of their clientele, made up of primarily British and American consumers. Economic historian Matthew Schandler (2005), in his thesis presented to the graduate faculty of the Louisiana State University, explains this dramatic decrease in trade between Switzerland and the Allied powers during the war:

The defeat of France and the construction of Germany’s counter-blockade caused a marked shift in Swiss trade relations. Between 1939 and 1941, exports to the Axis increased three-fold to Sfr. 577 million per year; goods to Italy doubled in value to Sfr.185.6 million per year. In comparison, goods to and from the Allies declined considerably. After the defeat of France, Switzerland exported goods worth Sfr. 91.4 million toFrance and Sfr. 23 million on average to Britain between 1939 and 1941. (p. 58)

Schandler also explains that to sell their products to the Allied countries during this Axis encirclement, Swiss companies often needed to go through extensive and costly smuggling “loopholes.” It therefore made financial sense for Rolex to look for selling opportunities within Axis territory, and prisoner of war camps – full of Rolex’s primarily British clientele – were obvious markets for the company to exploit.

[2]

Clive J. Nutting, a corporal in the Royal Corps of Signals (the British communications unit) was in France with the 44th Territorial division by the April of 1940 (Squires, 2006). He was then captured by German forces and eventually confirmed as a prisoner of war on September 12, 1940 (Antiquorum Auctioneers, Important collectors’ wristwatches, pocket watches & clocks, 2007). Eventually, after short internments at other prisoner camps, Nutting arrived at StalagLuft III sometime in 1942 and worked there as a cobbler repairing shoes for German soldiers and prisoners alike (Downing, 2007).

[3]

StalagLuft III was a prisoner of war camp for airmen, primarily officers, located 100 miles outside of Berlin in what is now Zagan, Poland, and reflects the specific type of internment camp to which Wilsdorf extended his offer. Materials in the U.S. Air Force Academy Library’s Special Collections explain that an officer camp, particularly StalagLuft III was “a model of civilized internment [where] the Geneva Convention of 1929 on the treatment of prisoners of war was complied with as much as possible” (Reed, n.d.). The prisoners in these ‘civilized’ camps became Rolex’s targeted market within Axis territory because they represented less of a financial risk than prisoners in other ‘uncivilized’ camps. For one, Rolex could expect that the prisoners at these civilized prisons would actually have the funds to pay for the watches they requested because Article 22 of the 1929 Geneva Convention required that “officers and persons of equivalent status [were to] procure their food and clothing from the pay to be paid to them by the detaining Power” (“Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 27 July 1929.” [1929 Geneva Convention], 2005). Therefore, camps that respected the Geneva Convention would be full of imprisoned officers who were receiving funds that they could use for the suggested purpose of purchasing clothing (or, indeed, watches). The fact that officers were receiving funds also explains why Wilsdorf extended his offer primarily to soldiers with officer status: not only was it logical for Wilsdorf to trust an officer’s word more than a lower soldier’s, but the Geneva Convention also ensured that officers had a considerable cash flow during the war (Downing, 2007).

Second, by targeting these ‘civilized’ camps, Wilsdorf helped ensure the successful shipment of his product. Article 37 of the 1929 Geneva Convention says, “prisoners of war shall be authorized to receive individually postal parcels containing foodstuffs and other articles intended for consumption or clothing. The parcels shall be delivered to the addressees and a receipt given” (1929 Geneva Convention, 2005). Therefore, by only sending the watches to the camps that upheld the Geneva Convention, Wilsdorf increased the chance of his product reaching the recipient and even secured a high potential that the delivery would be confirmed with a receipt.

[4]

Interestingly, C.J. Nutting, who was only a corporal in the British army, was an exception to Wilsdorf’s policy of only selling watches to prisoners with officer status. Nutting was likely afforded this exception because he ordered the Chronograph Oyster No. 122 watch model. Rolex’s Chronograph Oyster watch was very different from the model that was most commonly requested by British prisoners, which was instead a small, relatively inexpensive watch called the Speed King that was particularly popular for its size and price (Downing, 2007). Therefore, an order for the Chronograph Oyster No. 122, would have likely impressed Wilsdorf to the point of forgoing his policy of only selling watches to officers (Downing, 2007).

Moreover, Nutting most likely had the funds to purchase this expensive watch because he worked as a cobbler and earned money by repairing shoes while detained in StalagLuft III – something he may have mentioned in the multiple letters he sent to Wilsdorf while requesting the watch (Downing, 2007). Thus, while Nutting was not technically an officer, he was located at a “civilized” camp and had the money to pay for the watch, meaning that from Wilsdorf’s corporate point of view Nutting was just as attractive a client as an officer would be. Nutting did receive his watch (reportedly, by August 4, 1943) and his Chronograph Oyster No. 122 was recently sold in 2006, along with the letters sent between Wilsdorf and Nutting (including this transcribed document), for $65,000 (Cockington, 2006).

[5]

By underlining the words “you must not even think of settlement” in this receipt, Wilsdorf called attention to the virtuous side of his marketing proposal. While these underlined words are promptly followed by, “during the war,” indicating that Wilsdorf certainly expected to get paid back for the watches eventually, the generous and trusting aspects of his offer should not be ignored. He was sending his product out to British soldiers for free and taking the men at their word that they would eventually pay him back, which Nutting did when he returned to London in 1945 (Downing, 2007). Moreover, Wilsdorf was undoubtedly boosting the prisoners’ morale, since he was sending them a gift at no immediate cost.

Interestingly, Wilsdorf may have helped the British prisoners in more ways than he expected. In addition to boosting morale, watches were also important tools used during prison escapes; including the escapes from the camps where Wilsdorf had sent his Rolexes. StalagLuft III in particular was the site of multiple famed escape attempts: two examples, which have now been made into major blockbuster movies, were the Wooden Horse Escape in the Fall of 1943, and the “Great Escape” which took place on March 25, 1944. While it is a stretch to suggest that Wilsdorf intentionally contributed to these escapes, it is safe to say that he favored Allied soldiers enough to offer them this generous deal.

[6]

This letter contained the actual signature of the Hans Wilsdorf, which shows how this CEO personally handled these Rolex sales to prisoners of war. This personal involvement further suggests that Wilsdorf sympathized with the Allied cause, which in addition to his generous offer, is reflected in the efforts he made to forward letters between captured Allied soldiers and their families. His sympathies are also reflected in the fact that despite his German heritage, Wilsdorf openly spoke out against the Nazi regime (Downing, 2007). Therefore, while his dealings with POWs may be motivated by corporate gain, it is clear that he truly did care about the imprisoned Allied men.

References

Antiquorum Auctioneers, Important collectors’ wristwatches, pocket watches & clocks. (2007, May 13). Clive Nutting’s POW StalagLuft III watch: lot 311 [Press release]. Retrieved March 06, 2011. http://catalog.antiquorum.com/catalog.html?action=load&lotid=311&auctionid=163

Cockington, J. “Time on Your Hands.” Sydney Morning Herald, 27 September 2006. Retrieved March 06, 2011. http://www.vintagetimes.com.au/news/time-on-your-hands

Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 27 July 1929. (2005). International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). Retrieved April 06, 2011. http://www.icrc.org/ihl.nsf/FULL/305?OpenDocument

Dennis, M., Dillon, A., & Stephens, C. (n.d.). “Revolution on Your Wrist.” Smithsonian Online Publication. Retrieved March 03, 2011. http://americanhistory.si.edu/about/pubs/dennis1.pdf

Downing, A. (2007). “A ‘POW Rolex’ Recalls the Great Escape.” TimeZone. Retrieved March 06, 2011. http://www.timezone.com/library/extras/200704246126

Han’s Wilsdorf Founder of Rolex in 1908 [Web log post]. (2009, March 22). Retrieved March 12, 2011. http://rolexblog.blogspot.com/2009_03_01_archive.html

Jones, G. Hans Wilsdorf and Rolex. Master’s thesis, Harvard Business School, Harvard University, 2011.

Liebeskind, D. “What Makes Rolex Tick?” Stern Business Magazine, 2004. Retrieved March 06, 2011. http://w4.stern.nyu.edu/sternbusiness/fall_winter_2004/rolex.html

Reed, D. United State’s Air Force Academy: The Story of StalagLuft III. n.d. Retrieved March 06, 2011. http://www.usafa.edu/df/dflib/SL3/SL3.cfm?catname=Dean%20of%20Faculty

Schandler, M. The Economics of Neutrality: Switzerland and the United States in World War II. Unpublished master’s thesis, Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, 2005. Retrieved March 05, 2011. http://etd.lsu.edu/docs/available/etd-11162005-210229/unrestricted/Schandler_thesis.pdf

Squires, N. “Great Escape Mementos to Go Under the Hammer.” The Telegraph, 09 September 2006. Retrieved March 06, 2011. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/1528434/Great-Escape-mementos-to-go-under-the-hammer.html

Stone, G. The Watch. New York, NY: Abrams, 2006.

The “Prisoner of War” Watches from Rolex. Posted January 04, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2011, from http://grind365.com/random/the-prisoner-of-war-watches-from-rolex/