The myth of the Amazonian woman has been treated well by time. OriginatingRead More

Greetings from Herland

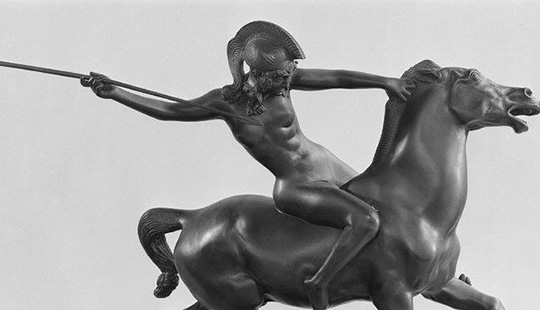

The myth of the Amazonian woman has been treated well by time. Originating as the recurrent Greek mythos of women warriors from the geographically unassigned land of Amazonia, towards the 16th century the myth received a rejuvenating shot of popularity. Informed by European explorers such as Francisco de Orellana, travelogues began to surface of bands of light-skinned women warriors who stirred fear in the hearts of native guides. Though there is certainly no singular author, the women of these tales were regarded as being fiercely independent, uncivilized, barbaric, and physically and sexually aggressive: they lived contentedly without men and outside of proper cities, dressed in scant clothes, had sex only as needed for the conception of girls, and brutally murdered any men that dared to approach or subdue them.

However, the question must be asked: Why were these women universally described as monumentally aggressive? These travelogues had far too much overlap, as well as input by the native men of varying cultures, to be informed merely by a deep-seated paternalistic fear of female independence. The famous naturalist and explorer of the late 18th and early 19th century Alexander von Humboldt, in his personal journal-style piece Personal Narrative of a Journey to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent, hypothesized, upon observing the similarities in the Ecuadorian Yagua tribe, that such reported sightings could have been run-ins with any number of the effeminate or maternalistic tribes of the Amazon basin. What this means for retrospective analysis is that there is an anthropological basis for why these women acted this way, beyond a mere superimposition of cultural fears. I propose that such an anthropological basis for their dynamic can be found in their relationship to their environment, and that such a connection can be shown to explain later developments in the notion of agro-ecology (the ecological approach to food production) as a means to further the cause of feminism.

It is important to establish that the Amazonian jungle women engaged in violent and aggressive acts not by choice, but as a function of survival that their relationship with the environment provides for. Assuming that their existence was informed by the practices of those tribes that lived in and amongst the Amazon basin in the 16th and 17th centuries, their method of food production would make them hunter-gatherers: humans who foraged for food amongst the undergrowth and hunted animals. As a hunter-gatherer, one has no control over the variables, only reliance upon nature to provide food, and aggressive exertions of rudimentary power, to survive anything you confront. When nature hands you a flood, your food source is in peril; if an animal decides you are to be its lunch, you must quickly make it yours. The Amazonian jungle women’s established relationship with their environment is dependent and reactionary.

In Herland, however, we see a slightly different dynamic play out. The novel follows a group of male travelers—the forceful chauvinist Terry Nicholson, the sensitive idealist Jeff Margrave, and the philosophical narrator Vandyck—who, much like the travelers who spawned the myths of the Amazonian jungle women, are lured into exploration by native tales of an isolated society of women without the need for men. Upon becoming the society’s first male visitors in centuries, the men settle in and become acquainted with the women, their history, and their gentle way of life. An early 19th century vision of a lush and verdant isolated feminist utopia, the author Charlotte Perkins Gilman was, unsurprisingly, a noted feminist who espoused new ways of thinking in both her writings and her life. She took control of the way her life progressed and evolved, but was never a violent voice in the feminist movement. Early in her life, she decided to bear a child, yet pursued an amicable divorce because she felt she did not need to be married to be successful or content; her progressiveness even went so far as to one day see her live with her ex-husband’s wife. Accordingly, as fiction imitates life, the women in her novel are strong, formidable women who cherish motherhood and sisterhood over all. One of the most arresting images of this are the women that Terry names “the colonels.” When Terry and the men first are engaged by the colonels, Terry reacts to their show of command by struggling violently and firing his revolver:

Terry soon found that it was useless [and fired upward with his revolver]. As they caught at it, he fired again—we heard a cry—. Instantly each of us was seized by five women. … So carried, and so held, we came into a high inner hall … suddenly there fell upon each of us at once a firm hand holding a wetted cloth before mouth and nose—an odor of swimming sweetness—anesthesia (25).

Terry confronts them with violence, and is instead met with nonviolent subduement and tranquilizers. The women of Herland are therefore completely capable of violent defense—as their relative ease of subduement demonstrates—but abstain from violence and aggressive acts as a result of a choice, favoring instead to manipulate the situation by quickly and quietly removing the threat. However, it is not question of aggression or passivity that demarcates the Amazonian jungle women and the Herland women but a question of aggression or control; reaction or creation; dependence or interdependence.

In opposition with the Amazonian jungle women, the women of Herland control the variables in their life. When Vandyck Jennings begins to describe the men’s reactions to the entrance of the women’s dominion, he does not just offer that there are thick jungles before them, but that these trees are “‘food-bearing, practically all of them … the rest, splendid hardwood. Call this a forest? It’s a truck farm!’… [The] trees were under as much careful cultivation as so many cabbages” (15-6). Two pieces of information are striking and illuminating within this passage. First, that the women utilize cultivation techniques as a way of guaranteeing resources. Rather than the dependent lifestyle of the Amazonian jungle woman, placing faith on the continued abundance of nature to ensure them wood, for shelter and tools, and foragings, for food and sustenance, the women of Herland modify and maintain the trees to have a source of food supply and building materials whose bounty is far more reliant upon their participation in, and manipulation of, the jungle’s ecosystem. The women of Herland also do not need to trek for miles to obtain goods that are needed, only to the areas that they know they have cultivated. By choosing to cultivate the trees they are put in a creative rather than reactive mindset, for they have knowledge of both the precautions they have taken, that will ensure their survival and relative ease of life, as well as knowledge of their integral part in the production and facilitation of this circle of life they have created. They are not on constant guard, knowing they are bending to the whims of mother nature, but rather they take a position that is similar to mother nature in its nurturing and self-determinatory hallmarks; thus, they are able to exit the aggressive animalistic mindset of the jungle by elevating themselves to a higher level of control within the ecosystem.

Secondly, concerning this passage, it must be noted that the cultivated trees of Herland are directly compared to cabbages. In the agricultural practices of that day, and indeed those practices have carried over to today, large swaths of land were razed to make way for the tilled plots that bore such cruciferous vegetables as cabbages. In contrast, the trees of Herland are existing jungle trees which have either been replanted or maintained in their original space. One destroys the ecology of a space to ensure food for a society, while another at worst transplants it to ensure that same level of food. In terms of harm to the ecology of the land in the interests of agricultural production, the Herland way of guaranteed resources is far more preferable and sustainable; it represents an interdependent relationship with the fluxes of nature, controlling the variables they are given. While the farming practices of cabbages may seem wholly removed from the lifestyle of the Amazonian jungle women, some similarities can be seen in the idea of taking without replenishing. The women of Herland are replenishing the jungle by maintaining the trees they take ownership of, and as a result of this fairly uninvasive and controlling relationship with their environment they are able to live a contented, harmonious life; the Amazonian women forage and hunt with, through ignorance or lack of care, limited effort to in turn maintain their source, and as a result of this highly invasive relationship to their environment their life is lived from threat to threat. There is no peace for the dependent reactionary who does not take the system into her own hands to change.

To exit the isolated jungle for a moment, the idea of control through sustainable resource management, or the intertwining of agro-ecology and feminism, is one that has been explored more fully in recent years as a complement to the feminist cause. In Mary Mellor’s overview, “Feminism and Environmental Ethics: A Materialist Perspective,” she argues that women have an interest in the control and harmony of their environment, for the guarantee of its resources is a guarantee of freedom. To control the resources of the land that ensure life, she states, is to deny men that same control and to give women an undeniable authority and essential function; it gives them social capital that they can leverage for power in their communities. Gilman’s vision of a female populace that is self-sufficient and agro-ecologically sustainable was highly progressive for its time, changing the predominant image of feminism from independent, warrior man-eaters to independent, solution-seeking nurturers, and drawing connections between a better way of life, agro-ecologically, and a better way of life, politically.

The Amazonian jungle women’s model should not be heralded as the pinnacle of feminist achievement, but rather an unrefined predecessor that posed a question for Charlotte Perkins Gilman and those of the later agro-ecological feminist thought to answer. Though their physical actions were aggressive, the Amazonian jungle women were in fact entirely passive in their way of life, for they could not take ownership nor control of the variables that dictated their fate that existed in their environment. Gilman’s model is, instead, based upon complete control of one’s environment, but in a nurturing way that does not include draconian treatment. It is based on creation of opportunities by changing and controlling the system one finds one’s self in, ammending the subconscious ideal of constant, most often violent, reaction. Control, or creation, is power and progression; reaction is concession and regression. Gilman’s women represent formidable models of womanhood, and such a model is based entirely on their ecological relationship with their surrounding environment, an infant idea whose stirrings have been drawn upon and developed into a modern feminist political ideology of interdependence and resource control as a means of empowerment and, ultimately, control of one’s fate.

Works Cited

Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. Herland and Selected Stories. Ed. Barbara H. Solomon. New York: Signet Classic, 1992.

Humboldt, Alexander Von. Personal Narrative of a Journey to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent. Trans. Jason Wilson and Malcolm Nicolson. London: Penguin, 1995.

Mellor, Mary. “Feminism and Environmental Ethics: A Materialist Perspective.” Sustainable Agriculture and Food. Vol. 2: Agriculture and the Environment. Ed. Jules Pretty. London: Earthscan, 2008.