How do we reconcile our present identity with continuous movement of time, the incessant production of personal history? How do medium and genre modulate the expressions of this existential quandary?

From the Archives: Discontinuities

As much as I have avoided naming it directly, I am personally and artistically haunted by the past.

Specifically, I am occupied by the insurmountable distance between my present self and the thousands of past selves in its wake. My earlier creative work relied entirely on excavating the family archive for images of my childhood self, searching for some semblance of familiarity behind the eyes of a baby I couldn’t quite recognize. Having exhausted that strategy, I sought out more ways to collapse the present into the past in an earnest attempt to reconcile their differences. In recent memory, I’ve presented a copy of my high school diary to my high school arch-nemesis;2 I’ve obsessively archived notes from my Grandmother spanning nearly 3 years.3 How was I one thing then, but am another thing now? Am I a stable thing? Is anything? Is there a way to make it stop? I’ve employed a variety of artistic strategies to cope with the progression of time, the evolution of the self, the fallibility of memory, and have so far been unsatiated by any of my conclusions.

I ask the following of the Confluence archive:

On an existential level: How do we reconcile our present identity with continuous movement of time, the incessant production of personal history?

On an artistic level: How do medium and genre modulate the expressions of this existential quandary?

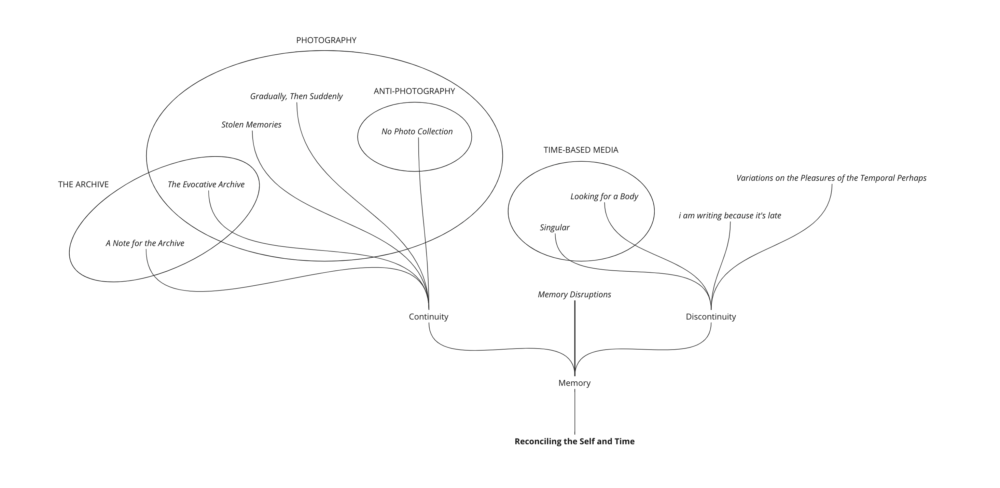

I believe it’s worth taking a nontraditional approach in excavating this archive in an attempt to understand the “vertical” associations between these works as opposed to their “horizontal” progression. To employ a traditional sequential timeline would be to disregard the conclusion of these pieces: that dissecting a subject diachronically is often circuitous, nonlinear, existentially fraught, and wound up in the dissector’s subjectivity. Embracing this, I don’t attempt to chart an evolution of ideology or method between these pieces.4 I’m more interested in the convergence (and divergence) of their interdependent conversations. The rigid divisions between past, present, and future become obsolete in service of this “vertical” understanding.

The most prominent vertical thread that links these works is their relationship to memory as a mechanism that reconciles (or tries to, at least) the current self with all its previous iterations. Memory creates narrative and cohesion, but is equally likely to induce a sense of discontinuity. As examined by James Huet in Memory Disruptions: The Body, the Sense, and the Self in Proust and Eliot, the act of remembering has the ability to unify the many selves by collapsing elements of the present with those of the past, as it does for the narrator of Proust’s Swann’s Way; He consumes a tea-soaked cookie which involuntarily induces a potent memory from his childhood, filling him with an “all-powerful joy.” In contrast, memory can also dismember the subject from itself, as it does in the case of Eliot’s “Rhapsody on a Windy Night”; The narrator is confronted with fragmentary impressionistic memories as he navigates a foreign environment, inducing a grotesque state of dissociation and non-linearity.

It is this schema of continuity vs. discontinuity that I use to dissect these archival pieces.

Works concerned with continuity often utilize or reference photography as a medium. There appears something solid and eternal about a still image, an objectivity that threads past and present into a coherent narrative. The photo series Gradually, Then Suddenly engages with this solidity on multiple levels as Amber Salik constructs a concrete narrative around her grandfather’s loss of his memory and, via that memory, his own concrete narrative of himself. The photos deepen and freeze time as it moves through the self, immortalizing it for future reference; the memory, the mode of reconciliation, becomes physicalized and stable. Similarly, Anna Ijiri Oehlkers conceptualizes the photos of strangers she acquires and archives as Stolen Memories. As Oehlkers explores, the photograph is less stable a medium than it appears—especially as it is subjected to her own fictions about its subjects and incorporated into her relationship to her own movement through time. Inspired by the found photographs, she begins to use a disposable camera, take more photographs, and create her own physical albums, all with the intention of creating images that will inevitably outlive and decontextualize her.

This idea of the archive also appears to be an appealing site to unearth continuity of the self—but, like photographs, archives are not particularly stable either. In The Evocative Archive, Vasi Bjeletich analyzes Kamal Badhey’s photo series, Portals and Passageways, in which the photographer takes on the perspective of her childhood self. Bjeletich highlights the innate subjectivity of the archivist role, specifically how the act of collecting, curating, and presenting a record is a creative act that alters the significance of its contents. Acknowledging the power of the archivist, Bjeletich advocates for a mode of archivism that embraces one’s specificity so as to become universal. In an evocative archive, the artist creates retrospective documentation as a way to stabilize the past, reconciling it with the present via collective memory. Katherine Leister finds a similar instability in her project A Note for the Archive. Archivism is often the “fetishism” of fragments (audio recordings, in Leister’s case) which are often presented as a coherent narrative despite the archive’s internal contradictions and general fallibility. The physicalized archive is as unstable as our memory, bringing the futility of continuity into high relief.

Lewis Fender embraces this discontinuity in their essay Variations on the Pleasures of the Temporal Perhaps. They mirror my existential plea, asking “If we are a culmination of all that has passed, but fact alone cannot furnish what has passed, then what are we?” Fender positions desire as an anachronistic mechanism that interpenetrates past, present, and future, collapsing temporality. Desire is volatile and nonlinear, as is the self, as is time. Xandi McMahon seems to know this intuitively in their piece i am writing because it’s late. Their desire-driven vignettes jump back and forth across the timeline, interspersed with quotations, phantasmic imagery, and asterisks. The stark divisions between sections seem to say, do not assume continuity. Despite many of these stylistic choices, the discontinuity of self is difficult to represent with a linear medium like text; the work will inevitably be read top to bottom, creating a kind of “order” or “narrative” even when one does not exist.

The time-based mediums utilized by Matt Yang and Melia Chendo (audio and video, respectively) seem the best suited for highlighting this kind of discontinuity. Yang creates several different recordings of Bobst Library to be played simultaneously, manipulating the progression of time by stacking it vertically. The listener is not allowed to progress forward linearly, instead trapped in an audioscape constructed from and existing outside of time; the past, present, and future are obsolete in their compression. Chendo takes the opposite approach, clipping time to replay it over and over, remixing it to highlight its mutability. With these mediums, time is manipulated, modulated, expanded, and recontextualized. Discontinuity is embraced as a tool for reconciliation, not as a threat to it; to reconcile the self with time is to admit that the self is discontinuous.

Each author or artist or archivist approaches the reconciliation of the self with time in a medium that is inevitably in dialogue with continuity (or lack thereof). Below you will find a selection of ten pieces from 2016 to 2023––although, as their archivist, I acknowledge that their selection and analysis was unobjective, a product of my discontinuous self.

- “Abby/Diary“/fn] I’ve asked artificial intelligence to interpret the events of a love affair, months dead;1“Psychoanalyze This Diary Entry“

- “If You Have Some Time Today…“

- Additionally, I acknowledge my innate subjectivity as their excavator/curator/dissector.